Part 1: The life of an American kestrel

The American kestrel is the smallest and cutest species of falcon found in North America. Other than their size, kestrels can be recognized by the beautiful rufous top side of their tail and back as well as the bold dark patterns on their head. Kestrels are sexually dimorphic, which can be seen in the difference between the sexes wing colours. The females have a dark rufous colour in their wings, while the males have light gray wings. They have a pale underside with a lighter dotted pattern, this likely helps them blend in with a brighter sky, so they aren’t seen by their prospective prey. Like many raptors, kestrels have a sharp hooked beak and large talons in order to more efficiently catch and tear apart prey. They generally have a shallower wingbeat and fly in lighter manner than similar species such as the merlin (Sibley, 2016).

Like most birds, American kestrels make use of vocal calls in their day to day lives. Kestrels have a common call that is appropriately higher pitched than other raptors and resembles a shrill killy killy killy (Sibley, 2016).

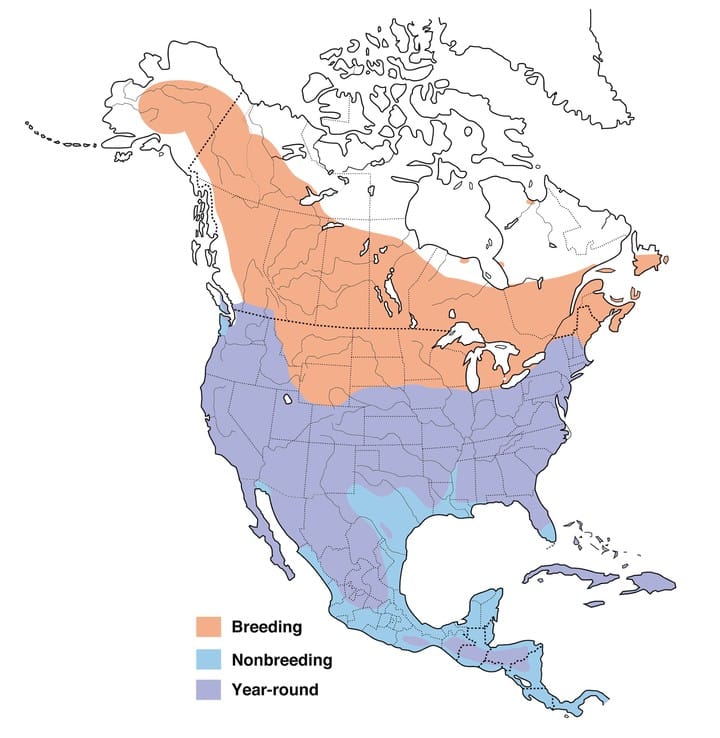

The American kestrel does as its name suggests and mainly frequents north and Middle America. It generally spends its breeding season up north, before moving south come winter as is popular with birds throughout north america.

The kestrel’s diet consists mainly of insects, small mammals and smaller birds. It hunts by hovering overhead before swooping straight down onto its prey. Kestrels just out of the nest can sometimes be seen hunting amongst one another and preening each other but will become less social as they grow more independent and proficient at hunting and maintenance (Varland, Klaas & Loughin, 1991).

One interesting feature of a kestrel is their tail bobbing behaviour, which is seen when they are landing, scouting for prey or just perching. Some species of birds, such as the elegant trogons have been shown to use their tail feathers for communication and breeding purposes. Research was done to see if the strange motions kestrels perform while perched were for similar purposes, but instead it pointed towards kestrels only engaging in their tail and head bobbing behaviour to keep their balance on their perches (Suich & Richison, 2018).

Like all birds, kestrels need to eventually nest and make even smaller kestrels. Kestrels are monogamous and both parents take specific roles in raising their young. The mother will devote most of her time to incubation of the young. The father will hunt, forage and protect the nest from anybody straying too close. Even though these roles are in play most of the time, there are still times when daddy dearest needs to spend some quality time sitting on his children while mom goes out (Liébana & Sarasola, 2009).

Photo by Anna Fasoli.

The kestrel population has been on the decline for decades. There have been multiple hypotheses given for the reason for their decline such as predation by the larger cooper hawks, habitat loss due to human development and the ingestion of toxic pesticides; But even with all these potential causes, nobody knows the exact reason for why kestrels are waning in numbers(Buskirk et al., 2017).

With the decline in the American kestrel’s numbers, efforts have been made to create more nesting habitats for them. This has been done using nests boxes, which give the tiny raptors a safe place to nest and breed even in places that have become devoid of natural cavities and hidey holes they would normally use. Nest boxes are also very useful for studying the number and behaviour of kestrels in a certain area. While studying kestrel using nest boxes brings the risk of disturbing them, it has proven very useful in being able to study these tiny terrors (Liébana & Sarasola, 2009).

Part 2: A Chemical toll on the Kestrel Life Cycle

As was mentioned earlier, pesticides and other toxic chemicals can take a toll on the health of American kestrels and may be one of the causes for the kestrel population declining in the past few decades (Buskirk et al., 2017).

Kestrels have been used in toxicology since the eighties with many scientific papers being made on the harmful effects that a lot of man-made chemicals and substances have on their reproduction and life processes. This is especially important for kestrels as they are particularly vulnerable to certain toxins (Franson & Rattner, 1984).

One early study was done on the effects of methyl parathion, a pesticide commonly used to control both agricultural pests and animal vectors for disease (Franson & Rattner, 1984). Their study found that methyl parathion was highly toxic and would intoxicate and kill the kestrels when given at rather low doses. In fact, the kestrel subjects were found to be at least twice as susceptible to the substance when compared to mallards.

While the last example is over 30 years old and the use of methyl parathion has thankfully been discontinued, there is still a need today to monitor the effects that manmade chemicals can have on these beautiful creatures. Fire retardants are another type of chemical that must be assessed for their toxicity to the wildlife they are used on.

One experiment used the feathers of American kestrels to gauge the amount of hexabromocyclododecane (a fire-retardant chemical used in Styrofoam that will hereby be referred to as HBCD) that the kestrel retains from the egg throughout its growth cycle (Marteinson et al., 2017). The reason that they can use the kestrels feathers that way is because of the way feathers grow. While feathers are initially growing, they are connected to the bird’s bloodstream until they are fully grown and cells in the feather fill with keratin protein and die off. The HBCD would then be present in the feathers themselves if it had been absorbed into the blood stream of the young. The feathers also allow for non-destructive sampling, which is to say no birds need to die for sampling to proceed. The parent birds’ daily diet consisted of cockerel meat that had been injected with the chemical in order to get HBCD into their systems. Feathers of the the parent birds’ offspring were then taken when they reached the age of nine months. They found that all the kestrels exposed still had the HBCD present in their feathers.

Photo by Carrie Threadgill.

The fact that the HBCD was passed on from parent to child is very alarming, as studies have already shown that it has adverse effects on male kestrels’ testicles and causes hypothyroidism (Marteinson et al., 2011). The effect of these chemicals could then be terrible for the kestrel’s ability to breed and may even contribute to the decline in kestrel population we have seen in North America. This is especially bad because HBCD has been used for years in Styrofoam production and has only started to be phased out in the past few years.

Photo by Jermaine Ong.

I hope this post has shown you how beautiful these birds are and how they need to be protected from these harmful chemicals. After all, from their behavioural ticks to their tiny stature to their cool, charismatic feather pattern, the American kestrel is one cool compact critter!

References:

Sibley, D.A. 2016. Sibley Birds West: Field Guide to Birds of Western North America Second Edition. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, New York. P. 258.

Varland, D.E., Klaas, E.E. and Loughin, T.M. 1991. Development of Foraging Behaviour in the American Kestrel. J. Raptor Res. 25(1): 9-17. Retrieved September 30, 2019 from https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/jrr/v025n01/p00009-p00017.pdf

Suich, J. and Ritchison, G. 2018. Possible Functions of Tail-Pumping by American Kestrels (Falco Sparverius). Avian Biol. Res. 11(4): 238-244. Retrieved September 30, 2019 from https://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/stl/abr/2018/00000011/00000004/art00003

Bó, M.S., Liébana, M.S. and Sarasola, J.H. 2009. Parental Care and Behaviour of Breeding American Kestrels (Falco Sparverius) in Central Argentina. J. Raptor Res. 43(4): 338-344. Retrieved October 1, 2019 from https://bioone.org/journals/Journal-of-Raptor-Research/volume-43/issue-4/JRR-08-82.1/Parental-Care-and-Behavior-of-Breeding-American-Kestrels-Falco-sparverius/10.3356/JRR-08-82.1.short

Buskirk, R.V., Heath, J.A., McClure, C.J.W., Pauli, B.P. and Schulwitz, S.E. 2017. Commentary: Research Recommendations for Understanding the Decline of American Kestrels (Falco Sparverius) Across Much of North America. J. Raptor Res. 51(4): 455-464. Retrieved October 1, 2019 from https://bioone.org/journals/Journal-of-Raptor-Research/volume-51/issue-4/JRR-16-73.1/Commentary–Research-Recommendations-for-Understanding-the-Decline-of-American/10.3356/JRR-16-73.1.short

Franson, J.C., Rattner, B.A. 1984. Methyl Parathion and Fenvalerate Toxicity in American Kestrels: Acute Physiological Responses and Effects of Cold. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 62(7): 787-792. Retrieved October 1, 2019 from https://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/abs/10.1139/y84-129#.XZa6yUZKjIV

Marteinson, S.C. et al. 2017. Transfer of Hexabromocyclododecane Flame Retardant Isomers From Captive American Kestrel Eggs to Feathers and Their Association With Thyroid Hormones and Growth. Environ. Pollut. 220(A): 441-451. Retrieved October 2, 2019 from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749116315202

Marteinson, S.C. et al. 2011. Diet Exposure to Technical Hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD) Affects Testes and Circulating Testosterone and Thyroxine Levels in American Kestrels (Falco Sparverius). Environ. Res. 111: 1116-1123. Retrieved October 3, 2019 from https://www.academia.edu/14497558/Diet_exposure_to_technical_hexabromocyclododecane_HBCD_affects_testes_and_circulating_testosterone_and_thyroxine_levels_in_American_kestrels_Falco_sparverius_

I really enjoyed your blog post! I also think that the American Kestrel is the cutest falcon. Its very interesting that they can check if HBCD is in the system by plucking feathers. Since HBCD can be passed down by parents to offspring, do you know how long HBCD stays in their systems for? Or is it there for life?

Hey Mason, really sorry about the late reply. While the paper i cited did talk about HBCD will bio-accumulate and that certain types of HBCD chemical have a greater persistence in organisms relative to others, there was no exact time frame mentioned. Keep in mind that i am no expert when it comes to toxicology in general, but I do believe that HBCD will eventually degrade and/or be expelled due to biological processes, but the damage it caused will likely stay throughout the lifetime of the subject.

Hi Johnathan,

Interesting blog. American Kestrels are absolutely adorable, and I love the video of their little tail pumping. So cute – I’d love to see one in the net at the banding station one day!

While I am familiar with the devastating effects of styrofoam in our marine ecosystems, I did not know about the effects that styrofoam had on birds, and more specifically the American Kestrel. Styrofoam truly is a horrible monster.

In your description of the study done on the transmission of hexabromocyclododecane in juvenile birds, I am a little unclear on how the the parents are acquiring the contamination. You mention that “the subjects’ parents were fed with cockerel injected with the chemical daily.” What exactly does that mean? Do you think there are other ways the researchers could have measured transmission of HBCD into young birds other than presumably injecting their parents with it?

Thanks,

Samuelle

Hey Sam, sorry for the super late reply! I initially worded that really badly, so i have gone back and edited that sentence for clarity’s sake. What i meant was the the parent kestrels’ day to day diet consisted of frozen cockerel meat that had been injected with HBCD. Therefore the parent kestrels took that HBCD into their system through ingestion. Thank you very much for catching that!

Hi John,

Nice blog! The American kestrel was my favourite bird from our Raptors trip so it was great to learn more about the species.

You mentioned that the Kestrel hunts by “hovering overhead before swooping straight down onto its prey”. I’m picturing that this is similar to what a Kingfisher does over water. Does the American Kestrel have a specific wing shape that allows for this hovering?

Thanks for the comment Olivia. While I didn’t really go into it in this blog, hovering behaviour in kestrels is a very interesting phenomenon. Kestrels don’t have particularly crazy wing shape, the main physical characteristic that helps them hover is the slotted feathers on the ends of their wings, which helps reduce turbulence and prevent stalling at low speeds. Aside from their size and wing slotting the most important adaptations for hovering are actually behavioural, kestrels will cock their tails down to slow themselves to a stop, while consciously flying against the wind in order to maintain lift. After that’s done it mainly just comes down to riding the wind, flapping to generate enough lift and adjusting their wings and tail to maintain altitude. I actually found a really cool youtube video showing it off here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7j6OsP7zL6w

Hi John.

I really enjoyed your article. And thank you for giving the detailed ID keys at the beginning! I have hard time ID-ing kestrels, so having to see it first really helps me remember them. Also it’s disturbing to learn that the HBCD makes it appearance so fast in the bird’s life history. I really hope that Nanaimo area is not as polluted as other areas that they will be more common in Nanaimo!

I wondered if the head bobbing is also useful for hunting or measuring the distance. Because I’ve seen a cat wiggle its head to accurately recognize the distance to the prey. Do you know if a kestral has a distinct head movement during its hunting flight because it chases such small maneuverable prey?

Hideki

Hi John,

Really great job on your blog! I loved the video on how the Kestrel pump their tail and bobs their heads. It is super interesting that it is connected to them maintaining their balance. I would never have thought that!

I was just wondering where exactly the American Kestrel is found nesting? I did my blog on the Peregrine Falcon and found that they were often nesting on cliffs and soaring far out into the ocean and I was wondering if it was similar for these little falcons.

Thanks for informing me on all things American Kestrel!

Danielle

Hi John,

I love the way your blog is written! It’s both informative and easy to read! And I agree, Kestrels are definitely the cutest raptor.

I had no idea styrofoam was so impactful to the environment, other than just as litter. Are there any other common products (other than plastic) that we take for granted that are negatively affecting the environment?

Thanks,

Sarah