Part 1: The Bird who cried Broken Wing

The Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus) is a shorebird in the Order Charadriiformes and in the Family Charadriidae, hence it is classified as a Plover (Baker, 2006). The Killdeer has the typical Plover features of a large and round head, large eyes and a short bill. The Killdeer takes on its own features as a slender bird with long legs, wings and tail. The Killdeer gets its name from calling “kill-deer” during mating displays. Otherwise, calls are a sharp “dee”. (Killdeer, All About Birds). As for colouration, KILL is brown or tan on its back and head and white on its belly and breast. The face is mostly brown with some black and white. The most distinctive features include two black bands on the breast, although downy juveniles have only a single breast-band, and an orange rump used in its feigning injury display that is explained below (Sibley, 2016; Killdeer, All About Birds).

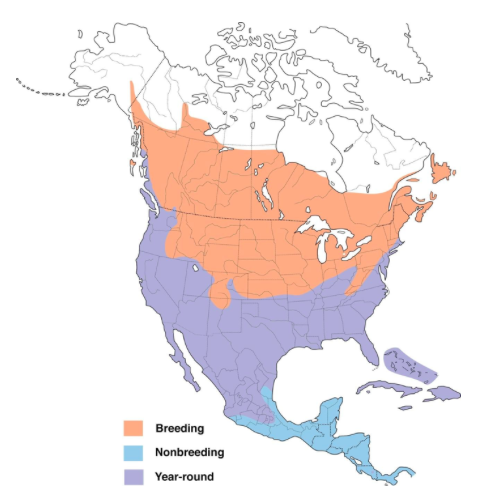

It’s relatively easy to spot Killdeer because of their distinctive features and their extensive range. The Killdeer is one of the most widely distributed birds over North America (Sanzenbacher and Haig, 2001). Individuals that breed in more northern regions migrate south for winter. On the other hand, individuals that breed in the southern U.S. and the Pacific coast are year-round residents and do not migrate (Killdeer, All About Birds). There is also a separate breeding population of Killdeer in South America, specifically Peru and Chile (Jackson and Jackson, 2000).

The local range of Killdeer also covers many different areas. Killdeer are shorebirds that eat invertebrates, most of which are insects. Therefore, they aren’t limited to shores and can inhabit dry areas as well. They are often found and nest on open ground, for example; fields, lawns and mudflats (Killdeer, All About Birds). They are tolerant of human development, so Killdeer nest locations can sometimes be in a not so convenient spot for humans (below). Nests are simple scrapes, or shallow depressions in the ground, usually 3-3.5 inches across. Four to six eggs are laid which will be incubated for 22-28 days by both parents (Quilliam, 1988). However, males have a greater role in parental activities than females (Brunton, 1990). Before nesting can occur, individuals (mostly males) must attract a mate. They advertise to the opposite sex by calling out, scraping the ground and taking short circular flights calling ‘kill-deer’ while flying with slow and deep wingbeats. Once the advertising individual has attracted a mate they begin to scrape out a nest together, followed by copulation. Once pairs are made they stay together for one or two years (Phillips, 1972).

If you haven’t seen Killdeer nesting, you’ve most likely seen their foraging behaviour. Individuals run along the ground and halt regularly as they search for insects and worms (Killdeer, All About Birds). Make sure to read below for more on research into Killdeer foraging habits. However, Killdeer nest protection behaviour takes the cake for amazing behaviour! Killdeer participate in parental defence. When a possible predator approaches the nest, the parents will use a series of ‘distraction displays’ to attempt to get the oncoming predator away from the nest and eggs. Both sexes use these distraction displays but male responses tend to be more intense than females. There are four different types of displays. There is the 1) crouched or upright run, 2) false-brooding, 3) injury feigning (broken wing display) and 4) threat display (Brunton, 1990).

False-brooding involves a parent pretending to brood on a false nest that is far enough away from their real nest. Injury feigning, specifically a broken wing display, involves the parent again getting far away from the nest then extending one or both wings about 30 degrees from the body, with its breast to the ground and tail fanned (Brunton, 1990). This position looks quite awkward and looks like the bird is too hurt to fly away, giving the illusion of an easy meal to an approaching predator. This hopefully gets the predator to change course onto the displaying parent instead and be lead away from the nest until the parent eventually flies away. The threat display, also called the ‘ungulate display’ (ungulate= large, hooved mammal) involves the Killdeer running towards the predator while holding the wings symmetrically out from the body with its head down and tail fanned (Brunton, 1990; Brunton, 1986). The threat display is known to sometimes be fatal to the displaying bird (Brunton, 1986). In one study, Killdeer successfully used these displays and distracted potential predators away from eggs and young about 99% of the time (Brunton, 1990).

Despite their nest defence success, Killdeer numbers have declined 47% from 1966 to 2014 (Killdeer, All About Birds). Some studies say that local populations are now increasing, but the overall population trend is still decreasing. Since the Killdeer has such a widespread range, it is rated Least Concern (BirdLife International, 2016). The significant declines in populations warrant future studies be conducted on the status of the Killdeer (Sanzenbacher and Haig, 2001).

The Killdeer

Part 2: Full Moon Party attendees

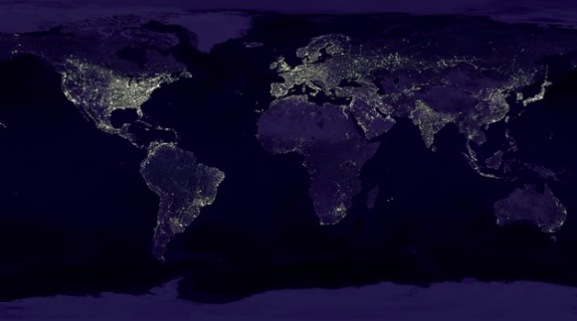

Electricity has become an essential part of human life. It allows us to extend our activities of the day into the night. However, like many other human innovations, this has an adverse effect on nature. It has been shown that artificial light alters the night-time regimes of nature, possibly extending or reducing the time available for activities of certain organisms (Davies et al., 2013). It has also been shown that waders (birds in the Order Charadriiformes) take advantage of artificial light to nocturnally forage for longer amounts of time than they could without artificial light (Santos et al., 2010; Dwyer et al., 2012).

Within the Order Charadriiformes, are the Plovers (family Charadriidae), of which the Killdeer is a member. Plovers need ambient light in order to forage because they rely heavily on their sense of vision and not as much on their sense of touch, relatively to Sandpipers (Martin and Piersma, 2009). Killdeer use the “foot-trembling” foraging technique, in which they stand on one foot and rapidly vibrate their other foot in the water and subsequently pick up any invertebrate prey they see stirred up to the surface (Smith, 1970).

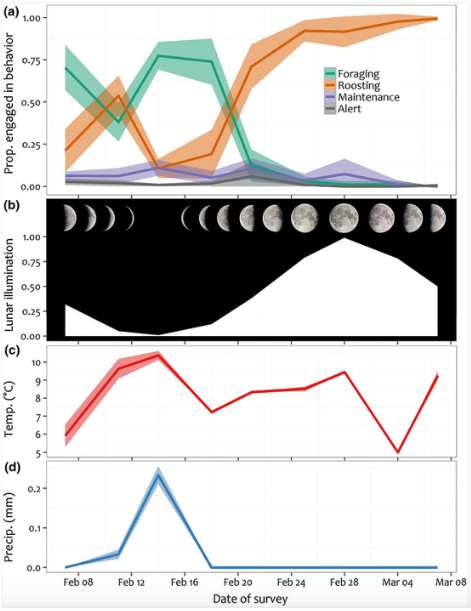

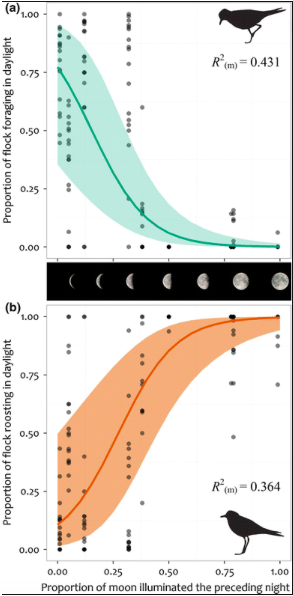

If artificial light is altering shorebird foraging habits, it makes sense that natural moonlight can affect their foraging habits as well. Studies have shown that Plovers (Killdeer and Black-bellied Plover) and Lapwings (a relative of Plovers) exhibit more individuals foraging during the day following nights with less visible moonlight and vice versa, less individuals foraging during the day following nights with more visible moonlight (Milsom et al., 1990; Colwell et al., 1997). Now, a new study attempts to explain why this trend exists (Eberhart-Phillips, 2017). The study states that increased moonlight illumination throughout the lunar cycle is allowing Killdeer to reap the advantages of nocturnal foraging.

Foraging at night instead of during the day may allow Killdeer to avoid diurnal (daytime) predators and have better access to their prey. Killdeer have large eyes that are good for vision in front of them but they do have a large blind spot over top of them (Martin and Piersma, 2009). This may make detecting predators from above difficult. Diurnal predation from other birds may be a good pressure for nocturnal foraging when these predators are not around. Additionally, Killdeer feed on invertebrates and their prey are most active at night. This could also be advantageous for Killdeer to forage at night because it may be easier and more efficient to forage for their prey at night than during the day. The reason they forage at night may be from either pressure listed above, or both (Eberhart-Phillips, 2017).

During the study, when the lunar cycle approached the Full Moon, there was more ambient light at night. The Killdeer were able to forage at night and subsequently do other activities, such as roost, during the day because their metabolic needs were already satisfied the night before. Inversely, when the lunar cycle approached the New Moon, there was less ambient light at night. The Killdeer were unable to forage at night and instead roost during the night and forage during the next day, when it is less beneficial to do so.

If Killdeer rely on patterns of the lunar cycle to forage, artificial light may actually be altering these pre-existing patterns. With more and more human development comes more and more light pollution. Killdeer are tolerant of human development so they may be even more so affected by artificial light at night than human intolerant species. With more artificial light, the Killdeer may shift their foraging habits to do so even more at night and shift amounts of organisms in the Killdeer food chain in the ecosystem. The Killdeer would most likely benefit as it would avoid diurnal predators more and be able to forage for prey more efficiently. The diurnal predators, like Raptors, may suffer from not being able to access Killdeer as a steady food source. Also, the invertebrates that Killdeer forage upon may become depleted as a result of the increased foraging of Killdeer. In conclusion, Killdeer are a cute and amazing species and more work needs to be put into both their population trends and the effect that light pollution may have on them.

References:

Baker, A. J. 2006, February 7. Plover. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 24, 2019, from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/plover

BirdLife International. 2016. Killdeer Charadrius vociferus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2019, from http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22693777A93422319.en

Brunton, D.H. 1986. Fatal Antipredator Behavior of a Killdeer. The Wilson Bulletin 98(4): 605-607. p0605-p0607.pdf

Brunton, D.H. 1990. The Effects of Nesting Stage, Sex, and Type of Predator on Parental Defense by Killdeer (Charadrius vociferous): Testing Models of Avian Parental Defense. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 26(3): 181-190. doi:10.1007/BF00172085

Colwell, M.A. and S.L. Dodd. 1997. Environmental and habitat correlates of pasture use by nonbreeding shorebirds. Condor 99: 337–344. doi:10.2307/1369939

Davies, T.W., J. Bennie, R. Inger, and K.J. Gaston. 2013. Artificial light alters natural regimes of night-time sky brightness. Scientific Reports 3: 1722. doi:10.1038/srep01722

Dwyer, R. G., S. Bearhop, H.A. Campbell and D.M. Bryant. 2012. Shedding light on light: benefits of anthropogenic illumination to a nocturnally foraging shorebird. Journal of Animal Ecology 82(2): 478-485. doi:10.1111/1365-2656.12012

Eberhart-Phillips, L. J. 2017. Dancing in the Moonlight: evidence that Killdeer foraging behaviour varies with the lunar cycle. Journal of Ornithology 158(1): 253-262. doi:10.1007/s10336-016-1389-4

Jackson, B. J. and J. A. Jackson. 2000. Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus), The Birds of North America. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.517

Killdeer, All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). Retrieved September 24, 2019, from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Killdeer/overview

Martin, G. R., and T. Piersma. 2009. Vision and touch in relation to foraging and predator detection: insightful contrasts between a plover and a sandpiper. Proceedings B 276(1656): 437–445. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1110

Milsom T.P., J.B.A. Rochard and S.J. Poole. 1990. Activity patterns of Lapwings Vanellus vanellus in relation to the lunar cycle. Scandinavian Journal of Ornithology 21:147–156. doi:10.2307/3676811

Phillips, R.E. 1972. Sexual and agonistic behaviour in the killdeer (Charadrius vociferus). Animal Behaviour 20(1): 1-9. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(72)80166-0

Quilliam, H. R. 1988. Killdeer. Hinterland Who’s Who. Retrieved September 24, 2019, from http://www.hww.ca/en/wildlife/birds/killdeer.html

Santos, C. D., A.C. Miranda, J.P. Granadeiro, P.M. Lourenço, S. Saraiva and J.M. Palmeirim. 2010. Effects of artificial illumination on the nocturnal foraging of waders. Acta Oecologica 36(2): 166-172. doi:10.1016/j.actao.2009.11.008

Sanzenbacher, P.M. and S.M. Haig. 2001. Killdeer Population Trends in North America (Tendencias Poblacionales de Charadrius vociferus en Norte América). Journal of Field Ornithology, 72(1): 160-169. doi:10.1648/0273-8570-72.1.160

Sibley, D.A. 2016. The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. Alfred A. Knopf, New York. 477 p.

Smith, S.M. 1970. “Foot-trembling” feeding behavior by a killdeer. The Condor 72(2): 245. doi:10.2307/1366650

This is really cool Olivia! I did not know that the killdeer got its name from its mating call, I thought it had a more gruesome background story.

Thanks for the comment, Cass! Yes I was expecting a more gruesome explanation as well but it turns out that the Killdeer is a cute and relatively harmless shorebird.

Hi Olivia,

Nice blog:) Killdeer are so common near my home and I have been seen their distraction displays many times. It’s pretty funny – they are great actors!

I had no idea that Killdeer populations have declined 47% form 1966. That’s insane! I also didn’t know about their foot trembling foraging technique. Very cool.

If Killdeer start foraging more and more at night, you mentioned that “diurnal predators, like Raptors, may suffer from not being able to access Killdeer as a steady food source.” Did you find any study that looked into this? I always see so many Killdeer foraging in the mud during the day – for now at least. How many diurnal raptors rely heavily on Killdeer specially for food?

Thanks, and again, good job.

Samuelle

Thanks for the comment, Sam! Yes, they’re definitely an entertaining bird to watch.

As for diurnal predators, such as Raptors, declining due to increased Killdeer night time foraging, this is only my broad speculation on what could potentially happen and i did not find any papers that looked specifically into this.

As for Raptors relying heavily on Killdeer for prey, I couldn’t find many papers on diurnal predation of Killdeer. I did find that there were instances of hunting and killing but I couldn’t find anything on the proportion of diurnal raptors diet that Killdeer make up.

Sources:

This article mentions two instances of Red-Tailed Hawk and one instance of Peregrine Falcon hunting Killdeer during their study. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-016-1389-4.

This article states that Merlin hunted Killdeer during their study and they found dead Killdeer with wounds suggesting Raptor attack to be the cause of their death. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1366760.

This article states that Merlin killed Piping Plovers, a close relative of Killdeer. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1522544.

Hi Olivia!

Such a great blog on such a cute bird! I was just wondering if you were able to find any information on what types of inverts killdeer are able to stir up with their “foot-trembling” technique?

Thanks,

Gen

Hi Gen,

Good question! I wasn’t able to find particular instances of foot-trembling food items but they do eat aquatic insect larvae. That would be my best guess for the environment that foot-trembling takes place in.

Killdeer, All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). Retrieved September 24, 2019, from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Killdeer/overview

Hi Olivia,

Great blogpost. I never knew how complex nest defense was for Killdeers and find the video of the broken wing display absolutely hilarious! My first reaction to viewing the display was to think that it would likely elevate the chance of predation on the displaying bird and offer the predator two meals for the price of one. It is astonishing that displays are effective at preventing predation 99% of the time.

Since broken-wing displays seem to be so effective, do you know if other shorebirds employ a similar strategy for nest defense or is this exclusive to Killdeers?

Thanks,

Jonathan A.

Hi Jonathan,

Thanks for the comment! Yes, many other birds use distraction displays, even the broken-wing display, specifically.

The Piping Plover, Lesser Golden-Plover and even non-shorebirds like the Alpine Accentor and the Mourning Dove are known to use the broken wing display.

Ristau, Carolyn. 1991. Aspects of the cognitive ethology of an injury-feigning bird, the piping plover. Cognitive Ethology: The Minds of Other Animals 91–126.

Byrkjedal, Ingvar. 1989. Nest defense behavior of lesser golden-plovers. Wilson Bulletin 101 (4): 579–590.

Barash, David. 1975. Evolutionary aspects of parental behavior: Distraction behavior of the alpine accentor. Wilson Bulletin 87 (3): 367–373.

Baskett, Thomas S. and Sayre, Mark W. and Tomlinson, Roy E. 1993. Ecology and Management of the Mourning Dove. Stackpole Books, p. 167