Part 1 : An introduction to Double Crested Cormorants.

Intro

Double crested cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus) belong to the order Suliformes and the family Phalacrocoracidae which has 38 species world wide and three species in BC (All About Birds). The name cormorant comes from the Latin words corvus and marinus meaning sea raven (Oceanwide-expeditions). Most cormorant species are associated with marine environments and the double crested cormorant is no exception however unlike most other cormorants it can also be found in inshore aquatic habitats. Double crested cormorants are highly adapted to aquatic habitats and are not to graceful on land.

Description and ID

Double crested cormorants are a large prehistoric looking water bird water bird. From a distance they can be identified by there all black plumage and long “S” shaped neck. Upon closer examination the yellow orange facial skin and striking blue eyes become more obvious. When swimming they float very low on the waters surface. When on shore cormorants can often be seen perched with there wings extended in order to dry them.

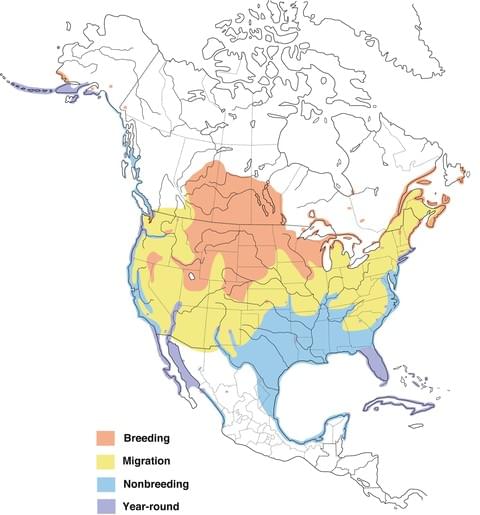

Habitat and Distribution

Double crested cormorants can be found in a variety of aquatic habitats across North America from Nearshore marine habitats to ponds, creeks or lakes (All About Birds) Double crested cormorants are also the only cormorant in North America that is commonly found inshore (Audubon). Along with aquatic habitats to fish cormorants also require areas to perch throughout the day, They spend nearly half their day resting and can be commonly seen sitting atop dock pilings, rocky outcroppings, or dead trees(All About Birds).

Diet and Ecology

Double crested cormorants are highly adapted to an aquatic niche and have many adaptations to help them thrive in there aquatic habitats. Their primary food is fish but they’ve also known to eat crustaceans such as crabs, shrimp, and crayfish as well as amphibians like frogs and salamanders (Audubon). To capture their prey cormorants dive underwater and chase down fish or other food items. To aid in diving cormorants produce much less preen oil that helps waterproof feathers and they lack barbicels that allow feathers to interlock, at first this may seem counter intuitive for an aquatic bird however letting water soak into their feathers makes them more dense and allows them to dive deeper and therefore better capture food. To make up for their feathers becoming water logged cormorants spend a significant amount of time drying their feathers by standing perched with their wings extended. Cormorants bones are also more dense compared to other birds serving a similar function of decreasing buoyancy for diving. Their feet are webbed far back on there body. Their feet are there primary mode of propulsion although they do sometimes use there wings. This makes them poor walkers on land. Their wings are also relatively short and with their high body weight they have the one of the highest flight cost of any bird.

Conservation

The double crested cormorant has experienced a number of population fluctuations driven primarily by human activity. When European settlers arrived to North America double-crested cormorants faced a major population decline. Cormorants were viewed as pest and were subjected to excessive hunting. Around the 1920’s to 1940’s the cormorant population began to rebound this was however as use of DDT became widespread in the 1940’s along with significant habitat damage the population experienced sever declines once again. The population remained low until DDT was banned in 1972 and Double crested cormorants were blue listed. Since then the population has increased and today double crested cormorants are considered a species of least concern.

Part 2: Parasite assemblages of Double-crested Cormorants as indicators of host populations and migration behavior

Due to presumed damages to fisheries cormorants are sometimes culled. Due to this it is important to be able to identify different populations that ranges can overlap during migration. To help identify different populations by analyzing the helminth parasites within the cormorants. These parasites are often site specific and therefore can be used to identify were the cormorants have been feeding. This can be help identify populations of migratory and non migratory birds and aid in the conservation of specific populations.

References

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2017. All About Birds : Double-crested Cormorant. [Internet]. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Double-crested_Cormorant/overview

Audubon: Guide to North American Birds. (n.d.) Retrieved November 5 2019. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/double-crested-cormorant

Wires, L.R. Cuthbert, F.J. 2006. Historic Populations of the Double-crested Cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus): Implications for Conservation and Management in the 21st Century. Waterbirds, 29(1):9-37

Oceanwide-expiditions : Cormorant. (n.d.) Retrieved November, 5 2019. https://oceanwide-expeditions.com/to-do/wildlife/cormorant-1

Sheehan, K.L. Tonkyn, D.W. Yarrow, .G.K. Johnson, R.J. 2016. Parasite assemblages of Double-crested Cormorants as indicators of host populations and migration behavior. Ecological Indicators. 67: 497-503

Hi Nathan,

Nice blog. I liked the video you included, that was really cool! Imagine getting to see that yourself! These guys are pretty striking birds.

I am curious about their breeding behaviour. Did you come across anything interesting in their breeding and nesting? Looking at the distribution map you included, I find it super interesting that these guys breed in the interior. I’m so accustomed to them being out on the ocean hanging out with the Pelagic Cormorants!

Thanks,

Samuelle

Hello Nathan,

Really neat blog, the video you added in was really interesting! I would never have thought that they would just dive down and pick off the sucker fish like that- a very efficient fishing method!!

Similar to Sam, I was wondering about their nesting behaviour. You said they can be seen drying off on the ground and up in trees after a swim. So, I was just wondering if they nest on the ground by the water or higher up in trees?

Thanks,

Danielle

Hi Nathan,

Very interesting article! I was especially interested in the use of parasite presence to determine feeding habitats of the migratory and non-migratory cormorants! I was just wondering if you came across anything that may have said which species are giving these cormorants their distinctive parasites?

Thanks!

Gen.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading your blog, Nathan! It is extremely well written!

I am wondering how they extracted the parasites from the birds in this study, did they use the culled cormorants post-mortem? Or cormorants that died of natural causes? I can’t imagine they were able to retrieve the parasites in living birds unless of course, they were external parasites?

Thanks!

Em

Hi Nathan,

Interesting blog, I enjoyed reading it! I am very interested in learning more about the parasites afflicting DCCO given that I am a parasite nerd and that we are both in parasitology. Tim mentioned during class that similar tracking was done in salmon by monitoring ciliophoran/myxozoan parasites. I assume that the parasite they used for this study was an endoparasite, but do you what it was? Was it a digenean trematode, and if so, what were the intermediate hosts?

Thanks,

Jonathan A.