When it comes time to breed, Great Blue Herons (GBHE) like to come together and form colonies (a.k.a. heronries) to mate and raise their young. They like to choose nesting sites that are fairly isolated and comfortably located within 2 to 4 miles of feeding areas. Swamps, islands, lakes, ponds, and rivers all make ideal nesting sites, as long as there are trees around to provide them with a place to build their elaborate nests. These nests can be as small as 20 inches or as large as 4 feet across and 3.5 feet deep. The GBHE spends a great deal of time carefully crafting the nest, spending anywhere from 3 days up to 2 weeks. These colonies can have upwards of 500 or more nests built hundreds of feet up in the trees (Cornell University: All About Birds). The North American Water bird Conservation Plan estimates a population of 83,000 breeding birds across the continent, and with such a high population, and need for nest sites, it is not surprising that nest sites are becoming more challenging to find. Human development and predation are two of the most important factors affecting nesting sites of this species.

Habitat loss due to human development is a huge threat not only to the GBHE but to all colonial nesting water birds that rely on aquatic foraging areas to feed during the breeding season and to nourish their young (Knight et al., 2016). With the human population increasing, there is a pressure to expand out and destroy these birds natural habitat. There is also the issue that water front nesting sites of the GBHE are also prime real-estate for the human population. For the Pacific Great Blue Heron, found in south coastal B.C., human development left them with one of two options, to tolerate the change or to relocate to other habitats. This is having a significant impact on the availability of suitable nesting sites that are both close to foraging areas and far enough away from human disturbances (Knight et al., 2016; Vennesland, 2010). Switching coasts and surveying breeding pairs of GBHE on the east coast, specifically in Maine, found the same effects, the number of breeding pairs declined by 64% between 1983 and 2009 (Auclair et al., 2015). Based on these numbers it is evident that without conservation strategies this species is in trouble. One foundation in New Brunswick has taken the initiative and created The Great Blue Heron Nesting Platform Project which provides temporary nesting platforms while they attempt to restore the natural habitat.

Not only does the destruction of nesting habitat impact the GBHE directly, but it forces all colonial water birds who rely on the same habitat to share the limited habitat remaining. Well established water bird colonies provide multiple species with the necessary resource of nest sites. Development is herding these water birds towards a decreasing number of suitable sites and forcing them to compete amongst themselves for the sites. This interspecific territoriality may reduce individual reproductive success and have greater consequences for the overall population (Wyman & Cuthbert, 2015).

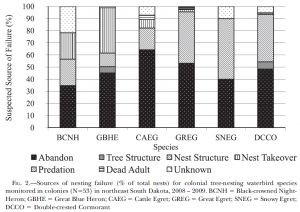

This graph shows the different ways nesting is being affected in multiple species of colonial water birds. The GBHE is mainly affected by abandonment, and nest takeover by other birds

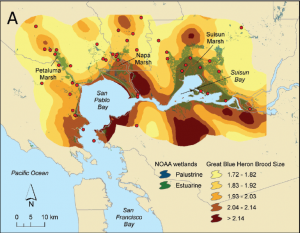

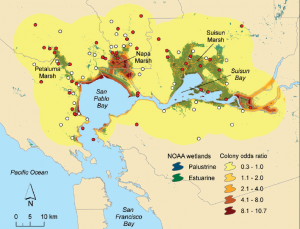

Although populations of GBHE have been rising in the past couple years, in 2008 and 2009 the sample population of GBHE in a study done in South Dakota revealed an overall nest success of 58.2% (loss due to abandonment of the nest) and an overall fledge success of only 35.9% (loss due to nest structure failure as well as death of young). Disturbances, whether caused by humans or a result of predation, led to nest abandonment and decreased reproductive success (Baker & Dieter, 2015). These findings were in agreement with another study that determined GBHE colonies were more likely to be found close to suitable foraging sites, but were found farther than expected when human development was interrupting their path to the sites. As seen in the figures below, the one on the left shows the brood size in relation to optimal foraging areas and the one on the right shows where colonies are expected to be found, in white, and where they are actually found shown in red (Kelly et al., 2008).

These maps show the importance in preserving and restoring wetland habitats in the hopes of providing successful nesting sites, foraging areas and opportunities for new colony sites for the GBHE as well as other colonial water birds.

Although habitat destruction has been the leading cause for loss of nest sites in the GBHE population, predation by the Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) on the GBHE eggs is also of concern for reproductive success. There is no question that habitat loss can be minimized, and conservation efforts should be implemented to protect these specific nesting sites for all colonial water birds, but the increase in the Bald Eagle population may actually be helping the GBHE. It seems as though GBHE have been able to modify their nesting behaviour to take advantage of the increase in the population of their main predator. Since nesting eagles keep other birds of prey at a distance of at least 250m around their nest, GBHE have taken advantage of this safety net. If a heronry of GBHE nest in the range of only one eagle they are only susceptible to predation from that one, instead of multiple. It has been found that 70% of heron nests and 19% of heron colonies are located within 200m of eagle nests, and GBHE nesting close to the eagles nest had a greater reproductive success that those nesting further away (Jones et al., 2013).

It is safe to say that the GBHE are intelligent birds taking advantage of their own predator. However, there is still the potential for research to continue investigating impacts of human development on the nesting sites of the GBHE and increase conservation efforts to protect what natural habitat they have left.

References:

Auclair, M., Ono, K., & Perlut, N. (2015). Brood provisioning and nest survival of ardea herodias (great blue heron) in maine. Northeastern Naturalist, 22(2), 307-317. doi:10.1656/045.022.0207

Baker, N. J., Dieter, C. D., & Bakker, K. K. (2015). Reproductive success of colonial tree-nesting waterbirds in prairie pothole wetlands and rivers throughout northeastern south dakota. The American Midland Naturalist, 174(1), 132-149. doi:10.1674/0003-0031-174.1.132

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (2015). All About Birds: Great Blue Heron. [website] Retrieved on November 1, 2017 from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Great_Blue_Heron/id

Jones, I., Butler, R., & Ydenberg, R. (2013). Recent switch by the great blue heron ardea herodias fannini in the pacific northwest to associative nesting with bald eagles (haliaeetus leucocephalus) to gain predator protection. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 91(7), 489-495. doi:10.1139/cjz-2012-0323

Kelly, J. P., Stralberg, D., Etienne, K., & McCaustland, M. (2008). Landscape influence on the quality of heron and egret colony sites. Wetlands, 28(2), 257-275. doi:10.1672/07-152.1

Knight, E., Vennesland, R., & Winchesters, N. (2016). Importance of proximity to foraging areas for the pacific great blue heron (ardea herodias fannini) nesting in a developed landscape. Waterbirds, 39(2), 165-174. doi:10.1675/063.039.0207

Vennesland, R. G. (2010). Risk perception of nesting great blue herons: Experimental evidence of habituation. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 88(1), 81-89. doi:10.1139/Z09-118

Wyman, K. E., & Cuthbert, F. J. (2015). Species identity and nest location predict agonistic interactions at a breeding colony of double-crested cormorants (phalacrocorax auritus) and great blue herons (ardea herodias). Waterbirds, 38(2), 201-207. doi:10.1675/063.038.0210

These birds are very majestic! I found it really interesting to learn that the “heronries” actually take advantage of their Bald Eagle predators when selecting nest sites!! The complete opposite of what I would have expected. Do you know if the Bald Eagles still attempt to prey on the nests located within their range, or do they typically leave them alone? It’s great to see organizations such as the Nesting Platform Project make an effort to educate the general public on the nesting behaviour of the Great Blue Heron and provide them with these nesting platforms.

Thanks for your comment Chanelle! I found it very interesting that they take advantage of the Bald Eagle too. The research I looked at suggested that the Bald Eagle would still prey on the Heron’s eggs, however, it is greatly reduced because the Great Blue Herons nest in colonies. The parents in the colonies would produce alarm signals to warn others and fight off the Bald Eagle.

Very interesting Nicole. Similar associations exist between GBHE and Great-horned Owl, where an owl may nest right in the middle of a GBHE heronry. Perhaps this also confers some level of protection, although GHOW have also been shown to ransack GBHE nests – https://youtu.be/v7w7ERBQvfs?t=30s

Not for the faint of heart if you like heron kids.