Day seven began with an early departure from the town and island of Heimaey, the largest and only inhabited island in the archipelago of Vestmannaeyjar, commonly referred to as the Westman Islands. The day began smoothly, despite one of the students boots having been mistakenly taken by Tim. The sunny weather permitted views of the islands that were not available during our trip to Heimaey two days prior, also allowing a much more comfortable ferry ride back to southern Iceland as many of us felt quite sea sick on the trip out.

The first stop of the day was at a relatively well preserved lava tube known as Raufarhólshellir. Despite being closed since December due to the nature of previous self-guided tours proving quite damaging to the area, Tim managed to convince some of the tour guide staff to allow us to enter for a quick view of this phenomenal volcanic feature. The volcanic textures and apparent series of flows provided us with insight into how these type of structures form, and what they can tell us about previous volcanic events. The lava tube originally formed approximately 5,200 years ago, and is comprised of somewhere between 10-15 layers of volcanic flows. It is believed that the eruption lasted around two years, resulting in the main section of this feature extending about 950 meters long. The staff informed us that the land owner has decided that the cave would now have restricted access to limit damage and littering in the lava tube.

The next site we visited was the Hellisheiði geothermal power station, owned and operated by Orka Náttúrunnar (ON Power), which roughly translates to Our Nature, a subsidiary of Orkuveita Reykjavíkur (OR), or Reykjavik Energy in English. The plant is located within the southern portion of the Hengill volcanic system. This power station is the largest geothermal power plant in Iceland, and the second largest geothermal power station in the world. The bedrock in this region is mainly comprised of basic to intermediate extrusive volcanic rocks of the pre-historic (prior to the settlement of Iceland) Holocene geological epoch. At this geothermal plant, hot water can be extracted from geothermal sources and pumped to the nearby communities for both heat and hot water usage. Approximately 99.9% of the homes within Reykjavik and the surrounding area are heated geothermally. Additionally, these geothermal fluids can be to produce electricity in a similar fashion to how steam engines produce energy. The processes responsible for producing these hot fluids within the subsurface are directly related to Iceland’s tectonic and geographic placement, directly overlying both the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, and a stationary mantle plume. A self-guided tour of the facility helped explain the various contributing factors to Iceland’s world renowned geothermal capabilities. A brief film explained that approximately one third of Iceland is underlain by active volcanic zones. The video explained how energy is extracted as steam and water, and is used to provide both hot water and electricity to nearby communities.

One of the problems with geothermal electricity production are the by-products hydrogen sulfide (H2S) gas and carbon dioxide (CO2) gas. Despite the misconception that there is very little that can be done with these gases in a sustainable timeframe, Iceland’s primary energy providers have proven that these gases can be reinjected into fractures in the underlying basalt, which results in the crystallization of certain minerals (H2S -> Pyrite or Fools Gold & CO2 -> Calcite) within the span of two years. This allows gases that are harmful to the environment to be converted back into rock. This form of energy production has proven both sustainable, as geothermal energy is a renewable resource, and efficient as approximately 27% of the country’s total electricity is sourced from geothermal activity. Overall, these factors demonstrate how Iceland is a global innovator in both the harnessing, and utilization of geothermal energy.

The final leg of our journey for the day was a visit to the northern section of the Hengill volcanic system which is host to the Nesjavellir geothermal power station. Also operated by Orka Náttúrunnar, the Nesjavellir geothermal plant is the second largest geothermal power station in Iceland. Although we were not provided the opportunity to tour this facility, the surrounding region was abundant with well-marked hiking trails that provided an up close view of various geothermal vents and the volcanic rocks that make up much of Iceland’s geothermal areas.

Despite common knowledge that the majority of Iceland’s bedrock consists of typical basalt, the basalt that appears in these areas does not fit this description. Many of the rocks have been significantly altered due to the presence of geothermal fluids, and are consequently quite variable in terms of mineralogy and texture. Along our hike, we observed two or more altered basalts that do not fit the characteristics of typical oceanic crust.

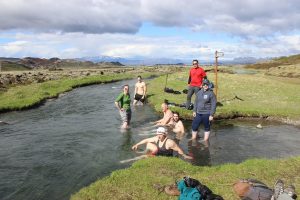

Just before returning to the bus, Tim made the observation that a regional map displayed the presence of a nearby river that was geothermally heated and could be used as a relaxing place to take a dip. Despite our excitement to see more geology and exciting rock formations, we quickly seized the opportunity and jumped right in.

This provided a momentary break from our research and the various stresses of field school, and reminded us of the once in a lifetime opportunity that this trip was providing. This also provided Alex with a once in a lifetime opportunity to take a selfie with Tim.

The drive to our hostel in Borgarnes was relaxing and provided all of us a well-needed opportunity to sleep, except for Tim who has been stuck with the responsibility of driving nearly the entire trip so far. What a day!