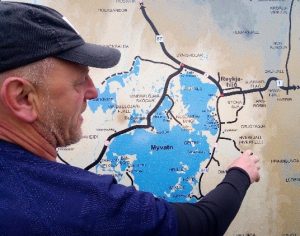

We started our 9th day with a short drive out east to the Myvatn Lake area. This region is packed with lots of geological goodies. We could have spent another day but had to cherry pick our stops. We took advantage of a lookout info map coming into the valley in order to get our bearings.

Our second stop of the day was where historic lava flows meet the Myvatn Lake. Here we found a collapsed lava tube and got to peek into the flow. The Krafla rift system is at least 300,000 years old, with many layers of lava flows and explosion craters. There are two historic flows in the area, the older being the Myvatn flow, dated 1724 to 1729. The Krafla Fires, the most recent eruption, occurred from 1975 to 1984. During these eruptions, magma was forced along fissures in the ground and erupted out along the surface as lava. Nine times during the Krafla Fires lava erupted onto the surface. More frequently the molten rock stayed within the fissures below ground. Throughout this time, magma filled the magma chamber below the surface and later erupted, causing the ground level to rise and fall respectively. It is estimated that 250,000,000 m3 of lava was erupted during the Krafla Fires (approximately 100,000 Olympic sized swimming pools). (from the Krafla Power Plant interpretive signage, 06/04/2017).

Our next stop was Leirhnjukur (clay hill), where geothermal fluid has altered the basalt to clay and other geothermal minerals. There was supposed to be some rhyolite around here but we didn’t get to see it. Despite the hotspring water being boiling hot, the day was very cold. Aaron even put a coat on! Highway reports put it at 4 degrees C before wind chill.

Very generally speaking, the geothermal fluids break down the basalt rock in the lava fields to create new colourful geothermal minerals; such as grey clays, yellow Sulphur, rusty red iron oxide, and white silicate minerals. Below shows where the geothermal area meets the Krafla lava flow.

With the weather and timing, we decided to cut our trip to the Viti Maar short and just snap a selfie. At least we got out of the car. Another tourist there just sent his drone to view the explosive crater that formed in the 1724 eruption.

Our next stop was to the Krafla Geothermal Power Station to warm up. This turned out to be quite an informative stop and we learned much about the technical aspect of generating electricity from geothermal water. The Krafla Geothermal Power Station is Iceland’s first and still the largest power station in the country. It currently produces about 500 GWh annually Construction of this power station began in 1974, but delays due to the Krafla Fires put back the official launch until 1977. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Krafla_Power_Station, accessed 06/06/2017). According to the interpretive signage at the power plant, 99% of the electricity produced in Iceland is renewable, being mostly either geothermal power or hydropower. They continue to innovate, with future ideas involving deeper wells and hotter water. Below is a shot of the different drill bits used to drill a geothermal well, as well as their method of dealing with a road-pipeline intersection.

Next stop was the mud pots near Namafjall Mountain. Námafjall is a very hot (80-100°C!) geothermal area just south of the Krafla geothermal power plant. Tourists flock to this little roadside stop to see its fumaroles and mud pots. It was quite beautiful with all the hydrothermal minerals. The tour busses were providing their patrons with little booties which would have been handy in keeping all the mud and clay off of our boots. We just went ‘low tech’ and used a handy puddle.

Besides basalts being broken down into fun new minerals, there were many fumeroles venting into the air. Along with steam, the fumaroles release hydrogen sulfide gas, which gives the area a particularly pungent smell if the wind has died down. In the past, Sulphur was mined from areas such as Námafjall to be used in the production of gunpowder.

Next stop was a rift called Grjotagja Cave. This one has a hotspring inside that was popular for bathing in times gone by but the Krafla eruptions increased the temperature so a dip in it now would not be fun. We were there for the geology but the tourists also like to come here as it was part of a scene in the popular Game of Thrones TV series.

Time being short, we decided to give Hverfjall crater a miss and skip over to Dimmugorgir.

Dimmuborgir is a labyrinth of towers that formed within a lava lake as the lava moved over water. The heated water generated steam which escaped up and formed towers. The towers were left behind as the lava lake was breached and remaining lava flowed out into channels.

There is a local legend about 13 troll brothers who live in Dimmuborgir and come out during the Yule season; sort of like a baker’s dozen of Santa Clauses. These characters have funny names like ‘Spoon Licker,’ ‘Sausage Swiper,’ and ‘Door Slammer.’ When they come out of their caves in winter to get ready for Christmas, you might spot them along the trails. (Taken from local interpretive signage and http://www.visitmyvatn.is/en/about-m-vatnssveit/winter, 06/06/2017)

At this point we were running late so had to do a quick lap through the labyrinth (with only a couple wrong turns) and head ‘home’ to Akureyri.