By Ellisif Hannesson

In Middlemarch’s cosmos, thread-like social pressures dominate individuals and their actions. How each character responds to their environment differs, with some individuals motivated by egotistical desires, while others attempt to live virtuously through altruistic behaviour. Notably, George Eliot excels at creating nuanced psychological portraits, making it difficult to label any character as purely villainous. Rosamond Vincy is a complex character whose self-serving and sabotaging actions lead many readers to characterize her as a villain. Yet this characterization is overly simplistic, as it fails to contextualize Rosamond within Middlemarch’s social ecosystem. While Rosamond is ultimately morally accountable for her actions, it is necessary to recognize the constraints of Rosamond’s patriarchal upbringing to fully understand the limited agency that shaped her behaviour. Gender roles are one of the most pervasive pressures in Middlemarch, which remained firmly entrenched in the social fabric of Victorian England. The text serves as a narrative lens for examining gender roles, which were polemically challenged by figures like Mary Wollstonecraft. In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Wollstonecraft contends that the lack of rational education for women results in their deformation, a cycle sustained and reinforced by the suffocating structures of patriarchy. The uneducated and incompetent woman Wollstonecraft depicts is akin to Rosamond’s education at a finishing school, wherein she learns merely to perform gender roles. In this way, Wollstonecraft offers a framework for analyzing Rosamond’s character in a sympathetic light. Through this lens, Rosamond’s educational background and behaviour elucidate the tragedy of how gender roles deform women and take away their self-knowledge, ultimately making Rosamond more of a victim than a calculated villain.

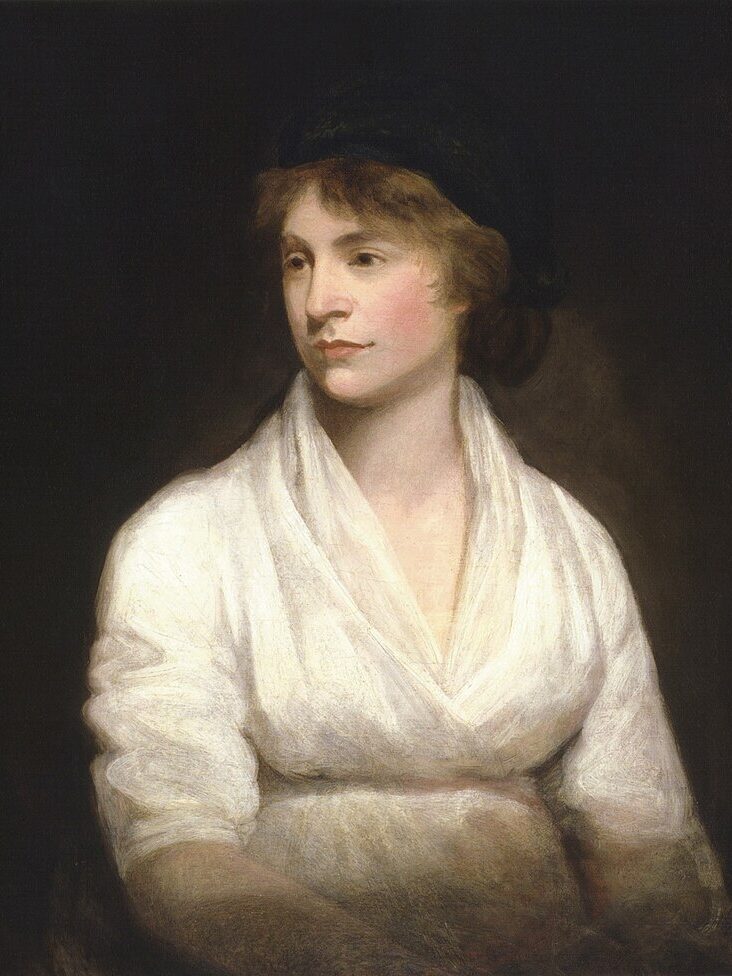

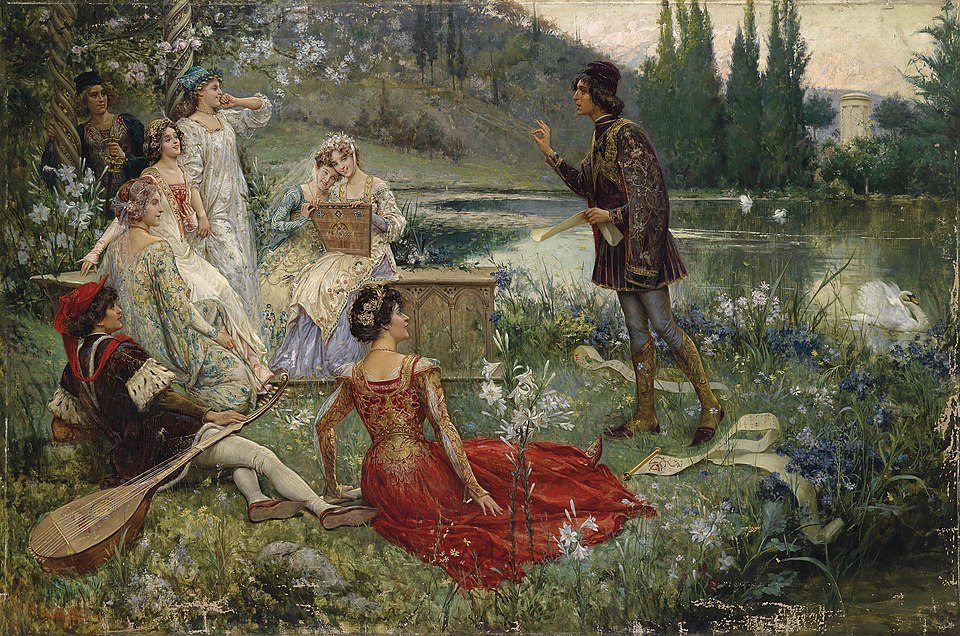

In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Mary Wollstonecraft critiques the prevailing system of female education in 18th-century society, arguing that it is a mechanism designed to sustain women’s subordination. While male education fostered rational thought, intellectual autonomy, and moral agency, female schooling was misdirected, emphasizing superficial accomplishments—music, drawing, etiquette, and ornamental knowledge—over critical reasoning. Thus, Wollstonecraft argues that the issue is not the lack of education but its distortion; the education women receive actively hinders their ability to develop reason, a faculty inherently part of their nature as rational beings endowed with souls. She further criticizes marriage as a structural mechanism reinforcing female economic and intellectual dependency, reducing them to ornamental roles and ensuring that “[women’s] time [is] sacrificed and their persons often legally prostituted” (41). Alternatively, Wollstonecraft envisions an education where women receive the same rigorous intellectual training as men, emphasizing logic, philosophy, history, and moral reflection. Such an education, she argues, is essential for developing virtue, which cannot be attained through passive instruction but must be shaped through rational inquiry and lived experience. “Knowledge of mankind,” Wollstonecraft asserts, “can be slowly obtained through experience,” and without intellectual cultivation, women are denied the ability to engage in moral reasoning (67). As Wollstonecraft makes clear, “to describe as virtuous anyone whose virtues don’t result from the exercise of his or her own reason is a farce” (14). This critique is exemplified in Middlemarch, where gender and education are central themes and struggles, framed within a lattice of social expectations that shape women’s roles.

This deprivation of adequate education emerges as a central form of oppression for women in Middlemarch. In Victorian England, societal norms imposed strict limitations on women’s access to rational schooling, and Eliot’s narrative vividly captures this restriction. Through the struggles of her central female characters, Eliot underscores the necessity for women to have access to genuine educational opportunities. Dorothea, for instance, is distinguished by her yearning for wisdom. However, Dorothea is unable to pursue this desire through formal education and instead turns to marriage as the only available avenue. Her decision to marry Mr. Casaubon can thus be seen as an attempt to fulfill her intellectual aspirations—though misguided. Had Dorothea had access to formal education, she would not have needed Casaubon to “liberate” her intellectually. Wollstonecraft criticizes this imperative, writing, “I recollect many women who, not led by degrees to proper studies … have indeed been overgrown children” (12). As Wollstonecraft further asserts, “women’s virtue must be comparable with men’s,” arguing that the perceived differences in intellectual ability between men and women do not arise from any inherent deficiency in women’s reasoning but rather from the unequal structure of their education (17). Rosamond exemplifies this critique, as her education—rooted in the performance of gender roles rather than genuine intellectual engagement—reveals how stunting female intellect inevitably undermines moral development, leaving both incomplete.

Rosamond’s formative education depicts the flawed educational model criticized by Wollstonecraft, as it fails to foster introspection or critical thinking, instead prioritizing the performance of gender roles. What distinguishes Rosamond from the other central female characters is that her educational background is explicitly highlighted early in the narrative, clearly contrasting the other women’s, such as Dorothea’s, more implicit or varied educational experiences. In her adolescence, Rosamond was praised as the flower of Mrs. Lemon’s school, where “the teaching included all that was demanded in the accomplished female” (Eliot 103). Rosamond’s education primarily consists of skills such as carriage etiquette, musical proficiency, and refined speech (Eliot 103). However, the practical utility of learning how to exit and enter carriages alone may be questioned in terms of its contribution to individual wisdom. Rosamond’s education fosters a myopic understanding of the world, training her to prioritize superficial charm over intellectual depth, thereby limiting her ability to navigate reality beyond societal expectations. This education mirrors Wollstonecraft’s critique on female education; when discussing men with her mother, Rosamond is told that “[a] woman must learn to put up with these things. You will be married someday” (Eliot 105). This instance illustrates not the moulding of Rosamond as an autonomous, critical-thinking individual, but rather the picture of a docile female whose life is centred around men. In absorbing this depiction of femininity, Rosamond adopts an inauthentic, performative persona that permeates her portrayal in Middlemarch, emphasized by the narrator’s recurring observation that she is “always having an audience in her own consciousness” (156). Such language explicitly suggests that Rosamond constantly performs for an imagined gaze. Therefore, the contextualization of Rosamond’s education illustrates the general upbringing of women in Victorian England as they learned to perform femininity.

As a result of Rosamond’s constructed character, she fails to achieve any self-knowledge and wisdom to guide her in behaving virtuously. The implication of performing gender roles indicates an underlying falsity—Rosamond’s character is not naturally submissive and ornate. Her character feels wildly inauthentic, which is exacerbated by depictions such as: “Every nerve and muscle in Rosamond was adjusted to the consciousness that she was being looked at. She was by nature an actress of parts that entered into her physique: she even acted her own character, and so well, that she did not know it to be precisely her own” (Eliot 119). This evidence reveals why Rosamond is so unique in her struggle with gender roles compared to Mary or Dorothea; her intrinsic disposition is that of a performer. Yet Rosamond’s plight mirrors that of a method actor so consumed by her role that her true self fades, eclipsed entirely by the character she performs. Though Rosamond is hyper-aware of others and their perceptions of her, she was never taught the value of education insofar as it leads to wisdom and virtue. Consequently, Rosamond grapples with adopting this superimposed picture of femininity and dealing with her natural inclinations. Gender roles are depicted as the correct embodiment—seeing as Mrs. Lemmon taught her “all that as demanded in the accomplished female”—and Rosamond considers herself the perfect woman by these standards (Eliot 103). However, Rosamond’s tragedy is the underlying implication of her dissatisfaction. Though Rosamond had been conditioned to believe this was a fulfilling life for a woman, she ultimately ended up unhappy in her marriage by assuming these gender roles. The narrator notes Rosamond’s dissatisfaction: “Rosamond’s discontent in her marriage was due to the conditions of marriage itself, to its demand for self-suppression and tolerance” (Eliot 581). Thus, by nature, Rosamond desires to express her will and have power over herself, yet does not possess the ability to truly know herself and cultivate virtue.

The characters’ reception of Rosamond’s actions highlights both her socioeconomic disenfranchisement and the extent to which patriarchal norms have profoundly shaped her. Wollstonecraft understands that knowledge is fundamental to character, and without adequate universal access, women will never meet their potential to be thoughtful, virtuous individuals: “[w]ithout knowledge, there can be no morality! Ignorance is a frail basis for virtue” (43). This reading explains Rosamond’s villainous actions by stressing that she was never given the opportunity to receive an education that nurtures her rational capacities. While it is crucial to recognize Rosamond’s accountability for her actions, it is pertinent to acknowledge the gendered dimensions inherent in her transgressions. Rosamond is undoubtedly responsible for her behaviour; however, her culpability is complicated by her ignorance and an apparent lack of moral grounding.

Rosamond’s actions demonstrate how her limited education shapes her behaviour. Take, for example, what could be considered her most reprehensible act: appealing to Lydgate’s uncle Godwin for financial assistance, a move that directly contravenes Lydgate’s wishes and provokes his intense anger at her subversive and self-serving behaviour. Rosamond’s decision is not merely an act of defiance but a manifestation of her deeply ingrained belief that personal charm and social maneuvering—not integrity, sacrifice, or hard work—are the proper means of securing stability. In doing so, she reduces marriage to a performance, in which material comfort and the avoidance of unpleasant realities take precedence over genuine commitment and shared responsibility. Godwin, too, is upset, yet notably, he addresses the letter back to Lydgate rather than Rosamond and instructs him not to “set your wife to write to me when you have anything to ask” (Eliot 520). Although Rosamond’s actions stem from a genuine desire to alleviate Lydgate’s financial burdens to acquire material possessions, this incident underscores the inequitable treatment she endures due to her gender. The dynamic between Godwin, Lydgate, and Rosamond reveals a layered conflict, but the gendered dimension is key: Rosamond’s voice and agency are dismissed precisely because she is a woman, making her intentions invisible and her efforts meaningless. In a society that prizes female submission, the ideal woman possesses neither voice nor agency. While Rosamond may have undermined Lydgate’s prospects for securing a future loan, the adjudication of her actions must be considered in light of her upbringing and circumstances. Therefore, the portrayal of Rosamond as an unalloyed embodiment of cold, calculated villainy is overly simplistic and fails to account for the constellated social and personal factors that shape her behaviour.

Rosamond’s final interaction with Dorothea reinforces the argument that her patriarchal education has fundamentally distorted her character to be self-serving, while emphasizing the transformative potential of a more substantive, less superficial education. Interpreting Rosamond as a product of her upbringing, influenced by her mother’s gossipy demeanour and societal gender norms, elucidates her momentary transcendence in the novel’s conclusion. This episode occurs in the final chapters of Middlemarch when Rosamond and Dorothea have a brief but pivotal interaction that contrasts their differing experiences of womanhood. Dorothea is a woman who achieves virtue by striving for knowledge; despite her endeavours, she still feels “that there was always something better which she might have done if she had only been better and known better” (Eliot 575-576). In this way, even Dorothea is not adequately educated to feel fully virtuous. Rosamond’s previous education had merely taught her how to perform gender roles; therefore, she was missing an education that goes beyond appearances. At this poignant moment between the women, readers receive the first and only authentic picture of Rosamond, as the narrator notes: “Rosamond, taken hold of by an emotion stronger than her own—hurried along in a new movement which gave all things some new, awful, undefined aspect—could find no words, but involuntarily, she put her lips to Dorothea’s forehead” (Eliot 612). The climactic interaction between the women crystallizes the notion that had Rosamond been afforded a genuine education grounded in substantive knowledge rather than superficial accomplishments, she might have had the opportunity to cultivate virtue.

A critic of Rosamond might counter this claim, suggesting that throughout the novel, she has consistently performed her actions with calculated intention, and this final scene is no exception—the narrator, too, subtly hints at such a reading. However, the previous portrayals of Rosamond’s actions were marked by a sense of performative artifice, suggesting that she is acutely conscious of her own manipulation. In stark contrast, the language in this pivotal scene evokes a sense of novelty and involuntariness, indicating a shift in Rosamond’s behaviour. Rosamond no longer calculates her appearance or outward conformity; rather, she appears to be focused on embodying virtue in a truer sense, learning empathy from Dorothea’s example in a manner that seems to transcend mere mimicry. Even if this moment is fleeting and does not fundamentally alter her character, it highlights the potential for moral growth within Rosamond—something that she has largely been unable to access due to her deformed education. This brief encounter suggests that, despite the limitations of her upbringing, Rosamond has a capacity for virtue, even if it cannot be sustained without a more substantial shift in her intellectual and moral development. While one moment of virtue does not equate to lasting change, the interaction underscores the possibility of empathy and moral transformation. Similarly, it is hardly surprising that Rosamond’s character arc remains stagnant: as Wollstonecraft argues, virtue demands ongoing engagement with knowledge and lived experience, and one brief albeit powerful instance cannot correct her deformities. Thus, while her character arc may not fully transcend her confines, this moment serves to illuminate the latent potential within Rosamond—a potential that her education has long suppressed.

Though Rosamond may present as villainous, her actions are deeply connected to her upbringing and education as a woman, which prioritized the performance of gender roles over imparting any substantive knowledge beyond superficial matters. In this way, Rosamond is the inevitable outcome of this patriarchal model of education that has eroded her potential. Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman offers a lens for understanding Rosamond’s deformed character. Wollstonecraft’s polemic posits that limitations imposed on women’s education hinder their capacity to evolve into virtuous, independent individuals. Despite Rosamond’s compliance with the expectations of her education, which sought to mould her into the model of accomplished femininity, her innate strength of will could not be entirely concealed. Consequently, Rosamond finds herself grappling with an inner conflict, uncertain of how to reconcile the discord within her soul and lacking guidance on how to address it. Perhaps the most unsettling part of Rosamond’s story is not her flaws, but the silent system that forged them—forcing us to ask how many more like her are condemned before they even begin. While Rosamond’s actions are undeniably shaped by the rigid constraints of her upbringing, her accountability for her moral failings cannot be dismissed. Ultimately, in understanding the tragic limitations of her education, we are left not with a simple villain, but a victim of a system that deforms both self and virtue, caught between the performance of a role and the silent yearning for a self she was never allowed to find.

Works Consulted

Eliot, George. Middlemarch. Edited by Gregory Maertz, Broadview Press, Ontario, 2018.

Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects. Edited by Johnathan Bennett, EarlyModernTexts, 2017, https://www.earlymoderntexts.com/assets/pdfs/wollstonecraft1792.pdf.