By Makayla Taylor

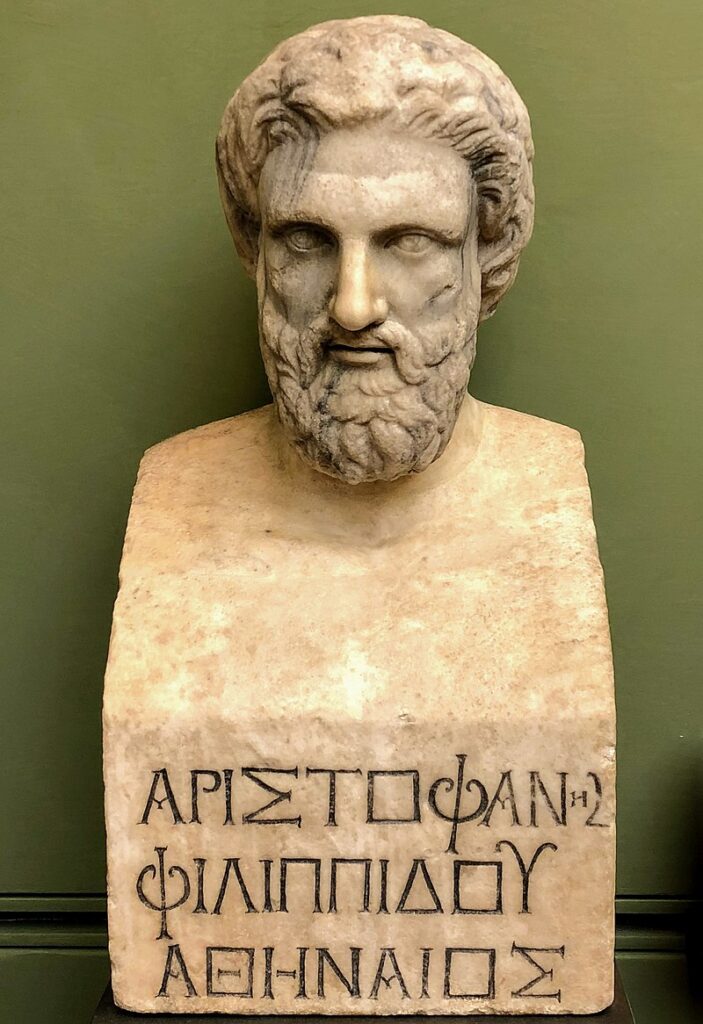

Exploring various perspectives on love, the Symposium is one of Plato’s most acclaimed works. Composed of a series of encomia concerning love, the text is structured as a dialogue, allowing characters to ask each other questions. One of the most influential speeches in this text is that of Aristophanes, who illustrates love through a myth regarding the history of humankind and the origin of soulmates. According to his account, humans were originally twice the size of present-day humans and spherical in shape. As punishment for their misbehaviour, Zeus halved each human, dividing one soul between two bodies. As a result, each person yearned for their other half—their soulmate. Aristophanes therefore proposes that love is a “pursuit for wholeness” (Plato 25) and that we seek fulfillment in reuniting with our other half. However, the other outlooks on love considered in the text at large suggest this is an insufficient theory of love. Eryximachus recognizes a difference between good and bad kinds of love. Diotima illustrates why love is not an end in itself, but a means to divine beauty and wisdom. Through these other perspectives on love, the reader is shown that Aristophanes’ speech simplifies love as a mere quest for wholeness. By telling a comic story about human nature, Aristophanes limits love to an exclusive pairing, fails to distinguish good and bad types of love, and disregards what love can lead to.

Portraying love as a quest for wholeness implies humans are lacking and can only become complete upon reuniting with their other half. While the notion of seeking soulmates can be considered beautiful or pleasing, depicting individuals as incomplete is a flawed element in Aristophanes’ theory of love. In fact, a paper discussing how eros relates to this idea of unfulfillment in Symposium, Chien-Ya Sun explains that this sense of lack is attributed to human nature, and states that, in Aristophanes’ myth, “the solution is pointed in one direction—a person” (494). Satiating our need for love exclusively through one person is problematic for two apparent reasons. Firstly, it narrowly defines love as the romantic kind, not accounting for other forms of love, such as familial and platonic, which are also greatly valued and should not be overlooked. Secondly, this approach to love is absolute, in the sense that lovers have no other pursuits once they find each other. In his speech, Aristophanes refers to the power of this loving devotion superseding the fundamental survival needs of two lovers: “they would not do anything apart from each other” (Plato 27). Although this may initially appear affectionate, love is depicted as a terminal phenomenon; once acquired, the lovers cannot ameliorate themselves through each other, nor can they cultivate their shared love. Instead, they forfeit everything else, leading to their death. Accordingly, if the solution to the incompleteness lovers experience as individuals is the love found through their other half, and once realized, results in death, humans spend their lives striving for a feeling of fulfillment that is fatal, as it stops them from seeking anything but each other. While Aristophanes employs a myth to illustrate his theory of love, another character in Symposium, Eryximachus, utilizes a metaphor.

Asserting that a bad type of love also exists, Eryximachus provides a more authentic account of love. Categorized into two contrasting forms, he compares the good and bad types of love to the “healthy and diseased” (20) conditions of the human body. As a doctor, the medical metaphor offers a clear illustration of his understanding of love. According to Philip Krinks in an essay examining technocracy in Symposium, the text includes the two types of love described by Eryximachus, which both work to attain a “telos,” an Ancient Greek term meaning goal, completion, or fulfillment (Brennan). To evince this claim, Krinks compares Eryximachus’ technocratic encomium with Diotima’s account of achieving telos by defining eros in relation to the good. Due to Eryximachus’ belief that doctors can manage eros in the body by encouraging “everything sound and healthy” (Plato 20) and foiling all that is “unhealthy and unsound” (21), Krinks claims that “Eryximachus envisages a good deal of success for the individual’s doctor in controlling eros” (9). Emphasizing the faith Eryximachus has in medicine, this passage highlights the complexities and fragility involved in love—a characteristic absent in Aristophanes’ speech. Furthermore, it also implies that by regulating eros, there is a goal to be accomplished, returning to the idea of completion. Comparing these two encomia reveals that Aristophanes’ outlook on love is idealistic and not comprehensive, as it approaches love from an optimistic point of view and fails to recognize the negative aspects of love as Eryximachus did. Additionally, Eryximachus’ interpretation of love does not romanticize it, but recognizes that it includes suffering, and therefore appears to be more relatable than Aristophanes’ account, who saw love through an unrealistic and positive lens, depicting an illusory representation premised on the quest for wholeness. Rather distinct from this contrasting portrayal of love as either good or bad, the following section analyzes the account of love presented by the only female character in Symposium, Diotima, who deems love as a vehicle to divine beauty.

Diotima, whose ideas are presented by Socrates, advances the purpose of love by describing it as a means to reach the divine, and emphasizes the importance of immortalizing love through reproduction. She suggests that love itself is not the final destination by illustrating the steps necessary to ascend the ladder to the divine, which is composed of different forms of love. In a journal article concerning the relationship between eros and the pursuit for absolute beauty in Symposium, Andrew Domanski postulates that Diotima shifts the attention from love to beauty. In reviewing the objects of love addressed by Diotima, he asserts that love is “the force or power which drives man onwards in his quest to realize absolute beauty, and so attain divine wisdom” (41). This passage captures the essence of Diotima’s discourse, as it delineates what love can produce, establishes love as a vehicle rather than a destination, and indicates that divine beauty and wisdom are of higher value than love by itself. As Diotima maintains that the object of love is to “possess the good forever” (Plato 52), seeking supreme wisdom over the wholeness resulting from the union of two people enables knowledge to become immortal. Humans should climb Diotima’s ladder of love not only to reproduce knowledge in beauty, but also to form a divine connection with the Gods. For these reasons, her account of love is more elevated than those of her peers. Moreover, she links love to the divine realm by sublimating love from an attainable goal to a fruitful process. Diotima’s depiction of love as something capable of reproduction and growth surpasses Aristophanes’ unadorned quest for wholeness, thus illuminating another aspect lacking in his speech. Although a sense of fulfillment can be realized from ascending Diotima’s ladder of love, the principal feature placing her theory of love above Aristophanes’ is the ultimate goal of immortal wisdom—a quality capable of growth superior to love itself, as opposed to the absolute completion felt upon acquiring love.

Reducing love to a pursuit for wholeness, Aristophanes’ speech circumscribes love to a romantic union between two particular people, fails to recognize two types of love, and neglects what love can beget. Analyzing the encomia in Symposium reveals the aspects in various theories of love overlooked by Aristophanes. Firstly, his notion of love as a quest for wholeness indicates humans are incomplete until they reunite with their soulmate. This suggestion not only confines love to a specific romantic relationship, but also errs by regarding individual human beings as inadequate. Next, Eryximachus divided love into two types: good and bad, both of which aim to attain a sense of fulfillment. However, Aristophanes did not distinguish between the positive and negative effects of eros, thus forming an insufficient theory of love. Finally, Diotima presents the most elevated theory on love, explaining love as a channel to the divine. Expressing how love can be immortal, she highlights what exists beyond love itself and, ultimately, what love can produce. Her multifaceted explication of love accentuates the simplicity of Aristophanes’ speech. While love can serve as a missing puzzle piece to one’s identity, it is full of complexities that a sense of completion alone cannot account for. The knowledge offered in Symposium provides meaningful insights into past perceptions of love, and allows readers to interpret and apply these perspectives to their understandings of love.

Works Cited

Brennan, Tad. “Telos.” Telos – Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2002, https://www.rep.routledge.com/articles/thematic/telos/v-1#:~:text=Telos%20is%20the%20ancient%20Greek,the%20modern%20word%20’teleology’.

Domanski, Andrew. “The Quest for Absolute Beauty in Plato’s Symposium.” Phronimon, vol. 13, no. 1, 2012, pp. 39-53.

Krinks, Philip. “The End of Love? Questioning Technocracy in Plato’s Symposium.” Archai (Brasília, Distrito Federal, Brazil), no. 29, 2020.

Plato. Symposium. Translated by Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff, Hackett Publishing Company, 1989.

Sun, Chien-Ya. “The Virtus of Unfulfilment: Rethinking Eros and Education in Plato’s Symposium.” Journal of Philosophy of Education, vol. 52, no. 3, 2019, pp. 491-502.