By Emma Wright

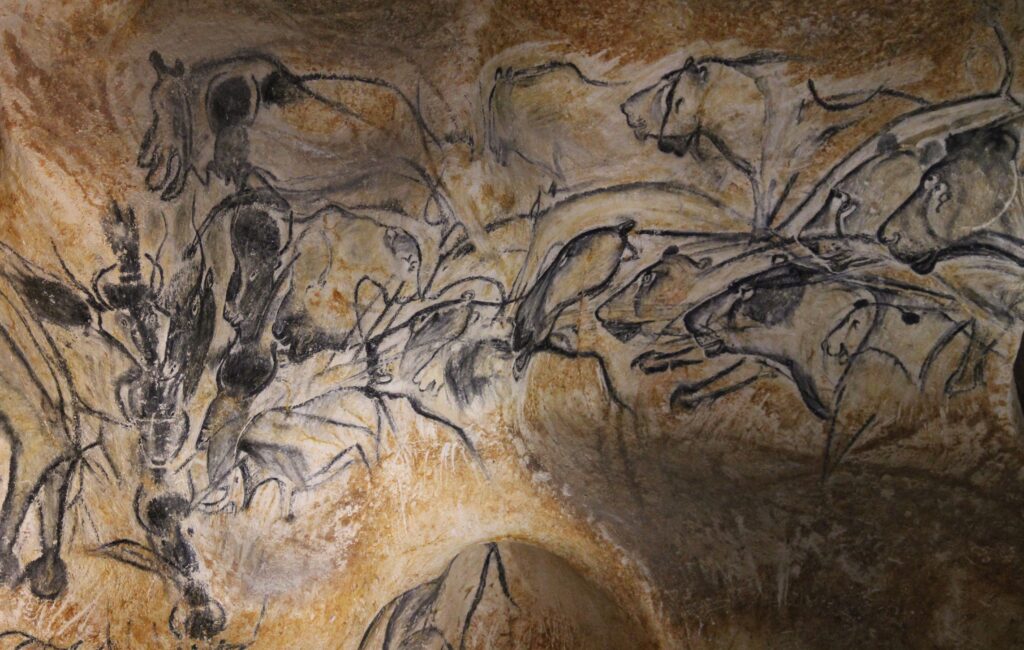

In The Origin of the Work of Art, Martin Heidegger claims that insofar as human beings make works like art, architectural structures (churches, temples, etc.), and tragedies, they allow for all things to be and to be meaningful. Humans are, therefore, an exclusive and fundamentally distinct group of beings. Heidegger says works have two essential features: “the setting up of a world and the setting forth of earth” (Heidegger 173). Works set up worlds because works are made to establish, enrich, or advance a way of life. This way of life is the world that any given group of historical people belong to, and this world is oriented around and consolidated by the works they make. Within the space that works make and worlds occupy, Heidegger thinks that all animals come alive for the first time. Animals belong to the earth, which “shows itself only when it remains undisclosed and unexplained” (Heidegger 172). This earthliness, or self-seclusion, of all animals is their essential feature, and it is only when animals are revealed by work within a world that they are noticed by humans and are, therefore, able to refuse to be known as any more than what they are immediately perceived to be. Without first being brought into the world, animals are merely unknown, and they flee from nothing. Yet—in CBC’s The Old Masters: Decoding Prehistoric Art with Jean Clottes, Clottes explains that the paintings in the Niaux Cave in the northern foothills of the Pyrenees and the Chauvet Cave in Vallon-Pont-d’Arc, Ardéche were made within a community that practiced shamanism (00:16:38-00:16:52). Because Clottes states that shamanism does not explain rock art directly, we cannot assume that cave painting was a shamanistic act. However, we can more broadly consider that the paintings were done by people who recognized the existence of non-anthropomorphic knowledge and power. While Heidegger thinks that works allow animals, and earthly beings more broadly (rocks, trees, etc.), to come alive and be what they are, in photos of prehistoric rock art like the Dabous Giraffes from 30,000 Years of Art, we see that animals and earth were first found meaningful and as a result, works were made. This means that work is not essential to set forth the earth, to make it manifest and meaningful, and thus that all things of the earth are not essentially self-secluding but exist objectively.

The first essential feature of the work is the setting up of a world. How does a work set up a world? Heidegger uses a Greek temple to illustrate his answer, “to erect means: to open the right in the sense of a guiding measure, a form in which what is essential gives guidance” (Heidegger, 169). But why is the setting up of a work an erecting that consecrates and praises? “Because the work, in its work-being, demands it” (Heidegger, 169). The ancient Greeks erected temples to harbour gods. These gods were essential to their culture. Hence, the temples were built piously, with devotion—what Heidegger calls a “consecrating-praising erection” (Heidegger, 171). Because of the temple’s importance, it “demands” to be built this way. The same piousness with which the temple is built is that which the temple consolidates in standing there: it is a place of great meaning for those whose world it belongs to, and they orient their way of life around it. It is because the temple is built for the sake of honouring the god who is essential to this particular world that the god can really exist within the temple. The temple itself “opens up a world and keeps it abidingly in force” (Heidegger, 171). It is not merely, as Heidegger points out, one fine day “added to what is already there,” nor is it a representation of what is essential, but is itself essential—the reason that this particular world can be the world that it is (Heidegger, 168). Without the temple, the god is lost, and the people lose their purpose, their culture, and their identity. In other words, the temple is not superfluous but holds great power. It “fits together and . . . gathers around itself the unity of those paths and relations in which birth and death, disaster and blessing, victory and disgrace, endurance and decline acquire the shape of destiny for human being. The all-governing expanse of this open relational context is the world of this historical people” (Heidegger, 167).

The second essential feature of the work is the setting forth of earth. How does a work set forth earth? Firstly, Heidegger thinks that earth is set forth in relation to and only in relation to a world. Heidegger says that as the temple sets up a world, it “causes [the material] to come forth for the very first time and to come into the open region of the work’s world” (Heidegger, 171). This means that within the space that a work clears by resting upon earth, the material from which it is built first comes to be noticed—it is brought into a world of anthropogenic meaning. For example, stone from the earth constitutes the columns of the temple, and therefore, the stone is noticed in its anthropogenic purpose, the only purpose it can have. Moreover, the earthly things which surround the temple or enter into its space also come to be for the first time: “Standing there, the building holds its ground against the storm raging above it and so first makes the storm itself manifest in its violence. The lustre and gleam of the stone, though itself apparently glowing only by the grace of the sun, first brings to radiance the light of day, the breadth of the sky, the darkness of the night” (Heidegger, 167-168). Here Heidegger means to say that without the temple the storm is essentially non-existent. Only when the temple towers up into the atmosphere does the storm first rage insofar as the storm has something—something important to humans—to rage against. Therefore, it is thanks to the humans who make the temple that the storm can show itself. These earthly things—the storm and the sun—can be what they are because of human-made work, because they are within a world where humans encounter them and from which they can flee.

What does it mean for the earth to be an earth? Heidegger writes, “Earth is that which comes forth and shelters. Earth, irreducibly spontaneous, is effortless and untiring. Upon the earth and in it, historical man grounds his dwelling in the world . . . The work moves the earth itself into the open region of a world and keeps it there. The work lets the earth be an earth” (Heidegger, 171-172). The earth can only be an earth when it is brought forth into the space that a world occupies: the bulky, spontaneous support of the rock is brought forth, first showing itself to be bulky and spontaneous as it lies underneath the surface area of the temple (Heidegger, 167). Importantly, Heidegger says that the earth must be brought forth without attempt to penetrate, calculate, or analyze it: “The earth appears openly cleared as itself only when it is perceived and preserved as that which is essentially undisclosable, that which shrinks from every disclosure and constantly keeps itself closed up” (Heidegger, 172). All earthly things are essentially self-secluding. That is to say that even if a rock can be weighed, it is not this number which is at all part of its essential nature. Indeed, the obscurity of its spontaneous support is its essential nature. Heidegger thinks that all animals and other earthly things are metaphysically different from humans and are, therefore, always fleeing from human understanding. They do this in two ways: “a refusal or merely a dissembling” (Heidegger, 179). For example, the backdoor opens, and the deer who stand in the snowy clearing of the yard eating the winterberries freeze, perk their ears, and dash into the forest beyond. They refuse to be seen and, at the same time, identify “the beginning of the clearing of what is cleared” (Heidegger, 179). Dissemblance, on the other hand, is the thin layer of ice upon a pond in late December. The pond presents itself as a place for solid footing until an unlucky step submerges one’s leg in frigid waters. However, it is only when these beings are first brought into a human-occupied space that they can self-seclude since their existence relies on human perception: if no one steps upon the seemingly solid surface of the pond, then the pond does not dissemble. If the deer do not first stand within the clearing of the backyard, they cannot flee from it. The space in which the human encounters the pond and from which the deer flee is the world, and it is set up by the work which humans make.

The artworks of one group of historical people—the prehistoric humans—show that Heidegger is wrong to claim that the earth requires a world to be what it is. While these artworks might have set up the world of these historical people, the earth did not become only in relation to this world because the artworks themselves were inspired by the earth. How could the work have set forth earth if earth inspired the setting up of work? Additionally, even if Heidegger thinks that “Tree and grass, eagle and bull, snake and cricket first enter into their distinctive shapes and thus come to appear as what they are” when work thrusts them into the world, because prehistoric humans noticed these beings prior to work and the world, it follows that “what they are” essentially is not self-secluding (Heidegger, 168). Heidegger writes, “Beings can be as beings only if they stand within and stand out within what is cleared in this clearing. Only this clearing grants and guarantees to us humans a passage to those beings that we ourselves are not, and access to the being that we ourselves are” (Heidegger, 178). But because animals appeared to prehistoric people before work was made, they appeared outside of any clearing. Since these beings appeared as themselves to humans without fleeing from any world, then their nature is not self-secluding. They are objectively meaningful rather than made meaningful by human-made work. For example, the stone is not merely meaningful because it constitutes the columns of the temple but is wholly meaningful in being stone, long before it is brought into the world and seen. And evidently, prehistoric artworks show that the natural reliefs of cave walls were found meaningful as they were, without human intervention.

One way in which these artworks show the objective being of earth is via their use of metaphor. In “Music,” Jan Zwicky writes, “Metaphors are rhetorical strategies in the service of ontological truth. A metaphor points to resonance among the internal structural relations that make one thing what it is and those that make another thing what it is” (Zwicky, 119). While Heidegger’s ontological theory posits that all beings are only in relation to human perception, Zwicky suggests that metaphors point to relationships which are mind-independent and so, by consequence, being that is mind-independent. Making metaphors requires being attentive to a given thing so that one may come to know what makes it what it is. Then, one can express the resonances one perceives among different things, among the “internal structural relations” of those things (Zwicky, 119). When a metaphor succeeds in “heightening our awareness of the echoes between things [and] our awareness of the things themselves,” it is because it says something true about the way that a thing is; for example, meeting Marea was catching a throw rope seconds before the waterfall or, the moss is a pillow wrapped in fresh linen (Zwicky, 119). Without meeting this dog, Marea, or myself, one knows a reality of our relationship. Without ever laying upon this bed of moss, one has. While Zwicky writes of metaphors as linguistic expressions, I do not think she would disagree that using natural reliefs on cave walls to create animals suggests resonance perception: a bison licking its flank is attended to; the peculiar form of the wall is attended to; and their structures resonate. In Dabous Giraffes, the narrowing surface of the rock face resonates with the giraffe’s elongated neck. When two converging lines painted on the cave wall are illuminated at a certain angle, and an ibex comes to life, we today stand before the wall and exclaim, “It’s an ibex!” by virtue of those two lines because prehistoric artists successfully perceived and expressed resonances among earthly things. If Zwicky is right, then this perception and expression depend on the intrinsic, mind-independent truth about the way that beings are, and here, again, earth is shown to be independent of a human world. These metaphors are expressed through images rather than utterances; nonetheless, making them requires great attention and imagination.

How these artworks were made also shows us that earth is objectively meaningful. Clottes explains that while many more paintings could have been made, it was important to the artists that the paintings were fitted to natural reliefs and cracks so that the animals on the walls could truly come alive. The fact that this was important to the artists is not hypothetical, Clottes explains, but evident because of the way they used the walls. The artworks do not bring forth the reliefs as Heidegger would argue; but in fact, the reliefs bring forth the artworks. Thus, much like the animals themselves, the cave walls appeared and were meaningful before work was made. Clottes also explains that in the Chauvet Cave, there is a small hole which infrequently leaks water but is impressive when it does, and surrounding it is a multiplicity of paintings—no coincidence, he says. Here, again, earth—a cave wall leaking water—was noticed, was found meaningful, and inspired artwork. Similar to the use of natural reliefs, in the Dabous Giraffes, we see the sunlight cast itself upon the engraved rock face and make prominent the giraffes’ spots as each one is encircled in its shadow. The editors write, “Each giraffe is engraved into a gently sloping rock face, the choice of location possibly a deliberate attempt to capture the slanting rays of the sun.” While Heidegger thinks that the work “first brings to radiance the light of day,” these historical people first found radiant the light of day and then used it to illuminate their artworks (Heidegger, 167-168). Indeed, the earth allows the artworks to be what they are. This is not only true sensuously—the way that the natural reliefs make the animals come alive and the sunlight paints the giraffes’ spots—but cognitively: all things of the earth make the artworks meaningful. Without their existence, these artworks would have never come to be. Therefore, it is shown to be impossible that human-made work sets forth earth, and it might be argued that, actually, it is earth which sets forth work.

Works Cited

Altamira Bison. Phaidon Editors, eds. 30,000 Years of Art, Phaidon Press, 2019, p. 15.

Heidegger, Martin. “The Origin of the Work of Art” (selection). Translated by Albert Hofstadter.

“The Old Masters: Decoding Prehistoric Art with Jean Clottes.” CBCnews, CBC/Radio Canada, https://www.cbc.ca/listen/live-radio/1-23-ideas/clip/15772888-the-old l.12-masters-decoding-pre-historic-art-with-jean-clottes.

Zwicky, Jan. “Music.” Aesthetics. Edited by Warren Heiti. Vancouver Island University, 2021, pp. 118-119.