By Kush Sachdeva

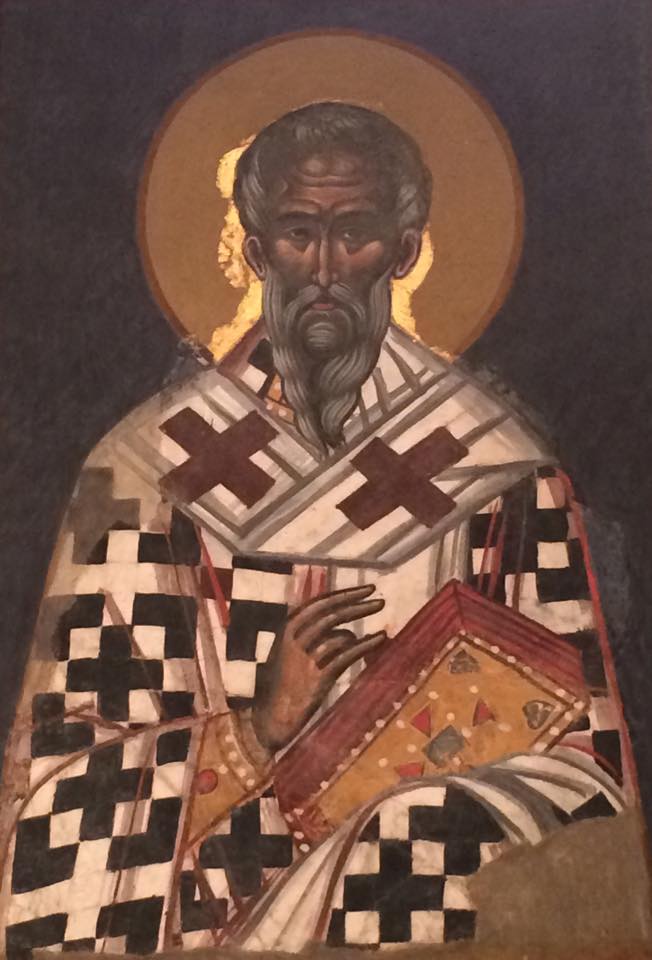

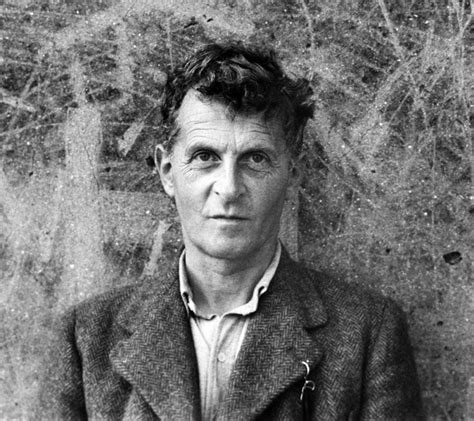

In this essay, I aim to show that the mystical path is not a journey but a surrender to the present moment where one does not stray from the mystical. This union transcends thought and desire, revealing the boundless simplicity beyond all inquiry. James Atkinson’s work, The Mystical in Wittgenstein’s Early Writings, and his lectures, inspired this idea. Rather than building on Atkinson’s work, this essay provides a gateway to the simplicity of the mystical in Pseudo-Dionysius’s work, additionally showing the simplicity of the mystical found in Wittgenstein’s early works.

Cataphatic and Apophatic Approaches and Their Limits

In theology, the cataphatic method of inquiry makes positive claims about God; meanwhile, the apophatic method is the negation of attributes of God. A positive claim is: “God is omniscient,” and a negation is “God is not limited by time or space.” These claims are about God, though the chasm of apophatic exhaustion does not convey what is beyond nullification. In other words, removing all that “God is not” does not tell us what God is. For instance, an eye does not describe the sound of a cloud bursting. Similarly, the experience of all other sounds does not explain the sound of a cloud bursting. Pseudo-Dionysius presents this idea in his conception of “God as every sensation, thought, and the maxim of reason” (1040D). God transcends sensation and reason, is beyond thought and sense, and yet embodies them. The idea here is the presence and attention of what happens to be; that is to say, God is not limited to intellectual activity like a cataphatic, apophatic, or any manner of inquiry but rather is present in both–intellectual and unmediated experience. Although the apophatic method aims to reveal aspects of God that exceed human conceptualization through negation, it reaffirms dualism by indicating that neither affirmation nor negation can wholly capture the mystical essence. Pseudo-Dionysius notes that God is not a being among beings but rather the source of being itself, affirming that God is not in a position in the space of empirical understanding but in the expanse of the undefiled now (1065).

Paradox of Apophatic Affirmation

The apophatic method unintentionally affirms through negation, revealing the limitations of positional understanding. For instance, stating that God is not X still places God in relation to X, echoing Pseudo-Dionysius’s assertion that the supreme cause of every conceptual thing is not itself conceptual, suggesting that causes reveal aspects of the supreme cause, they never encapsulate it fully (1033D). The supreme cause is not merely the primary or final cause, nor is it an amalgamation of all causes, a negation of observable causes, or a sum of causal relations—though it is present in all these. If one attempts to grasp the supreme cause through a higher-order, meta-causal perspective, this understanding will reflect the supreme cause but fail to encompass it entirely. Even if a meta-meta-causal understanding emerged, it would again point to the supreme cause without capturing its essence. This recursive pursuit highlights that the supreme cause transcends while encompassing all causes, ultimately negation as a limited means of inquiry carries an implicit affirmation.

Resolution of Paradox

Consider two definitions: (a) absence of a fourth boundary, negation of curves, denial of excess edges, does not conform to anything beyond its points, and (b) a triangle. The former (a) presents negative boundaries, and the latter (b) represents positive boundaries, raising a critical question: do different ways of inquiry provide a unique insight into the mystical? Pseudo-Dionysius would respond to this by mentioning that “all that is said of God is by necessity inadequate,” highlighting the challenge of understanding mystical attributes through language; this is further reflected in his contention that “It is in the abandonment of all that we find the path to the Divine” (553C, 593A). To look beyond both ways of thinking and approaching the mystical, one needs to tap into the heart of the hearts; in this moment of reaching the deepest, darkest part of experience, one recognizes the mystical as “preeminently simple and absolute nature, free of every limitation,” where every boundary falls short (1048B). The mystical moment transcends inquiry itself, making any method of approach a barrier rather than a guide. He goes as far as to claim that the intimate experience lies beyond all desire; desires are rooted in the expectation of a future, usually better than what happens to be now; by looking beyond desire, one is essentially forced to be fully present in the now (588A).

Mystical Surrender

The mystical does not emerge through surrender to the ineffable—an encounter that abandons reason while remaining intimately present. This surrender unfolds in the simplicity of the infinite moment where known and not known coexist. All potential states exist simultaneously, where experiencer and experience are inseparable, undivided by thought or perception. This resonates with the idea that one is not merely in the universe but is the universe experiencing itself; in this immediate now, distinctions dissolve, an ineffable state of epistemic-ontological ambivalence reveals, where the thinking self and the flux of experience are no longer seen as separate. This surrender represents experience unfolding from the center to the edge and the edge enfolding to the center; ultimately, the center becomes the edge, and the edge disappears into its origin. By resonating with this, a new being emerges, seeking to be present in the fullness of God’s absence, embracing the present hitherto neglected, wandering in the new world that reveals itself in the infinite tapestry of the abyss of what happens to be, for him all things find their completion in the mystical, even as they seem to vanish into nothingness (1089A). This surrender reveals that one does not merely surrender to the now but abandons what is not present; here, the essence of the mystical is a negative effort, requiring one to stand still and not lean in.

Mystical Awareness

From the standpoint of mystical surrender, a different realization of knowing emerges—expression. Wittgenstein remarks in the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, proposition 6.44, “It is not how things are in the world that is mystical, but that it exists.” Imagine analyzing the notes and the orchestra, but the true wonder of the symphony lies in the fact that it is mystical, realizing that the world exists, not necessarily why it works or what happens in it, but that it is. Mystical awareness eludes a concise description. For example, the question, “What is it about the symphony that you like?” cannot be answered without a form or manner of descriptions that reduce the experience to a concept that claims to express the symphony and what one likes about it. In proposition 6.522, Wittgenstein mentions, “There are, indeed, things that cannot be put into words. They make themselves manifest. They are what is mystical.” This idea can be understood through a fishing metaphor.

Imagine a fisher on a small boat on the ocean, fishing with a line. The boat represents the inquirer, the line represents intention, and the ocean is the vast unknown—the space of truth and understanding. As one casts the line into the water, it descends through layers of the ocean, metaphorically reaching toward the depths of knowledge, where the foundation of understanding lies hidden. The ocean is boundless, cradling mysteries that one can never fully comprehend, while the line, simple and linear, seeks to grasp what is unknowable in its limited capacity. As the line sinks deeper, it only experiences tension—the sense of movement, resistance, and occasional moments when something is caught, perhaps a brief glimpse of meaning or understanding. But the line, like the inquirer, cannot grasp the fullness of the ocean. It cannot understand the vastness of the waters nor the fullness of what is happening around it. In moments of doubt, the line wonders: What if there is nothing at the end of it? What if the waters are empty, and the boat drifts aimlessly? If there is no resistance or pull, what is its purpose? Can it continue fishing without a catch, or does it lose meaning? The line becomes a paradox—a simple thread stretching between the boat and the ocean, linking the finite with the infinite, the known with the unknown. It neither fully understands the ocean nor comprehends the depths it is connected to. Yet, it carries on, perhaps finding its truth not in control but in surrendering to the mystery of the unknown, acknowledging its limitations and continuing the search without ever fully grasping what it seeks.

Pathlessness

Pseudo-Dionysius shows that in experiencing the mystical, one does not seek inquiry while immersed in the fullness of unmediated presence beyond sensory or intellectual apprehension. In surrendering to the mystical, what can be said and the ineffable converge in the now, not disappearing but simply being. In this subtle interplay of grasping abandonment and abandoning graspable, the mystical does not become clearer; it simply is. To say otherwise—to claim that one must do certain things or climb hierarchies to attain mystical experience—seems conventionally true. However, anything that is a complex conjunction of words points to the symbolism of the words, not the reality itself. Words create pictures and mental representations, while the mystical resonates in the simplicity of the now, beyond the formation of mental images. In this space where words say the most they can, Wittgenstein’s summation of Tractatus echoes: “What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence” (7.0). The mystical, ever-present, reveals itself not through knowing, but in the silent space where inquiry dissolves. The mystical, like the supreme cause, is absent only insofar as one ignores its presence, all the while one emerges in the present.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the path to the mystical is no path. The mystical unfolds and enfolds in the idleness of what happens to be—where conceptual striving gives way to silent presence, and surrender opens the way to what is beyond thought and desire. The mystical moment is not an endpoint but an ongoing encounter with the infinite, where the seeker is not merely aware of the mystical but realizes the inseparable nature of the mystical’s unfolding presence. In this space, the mystical ceases to be a pursuit and becomes the fullness of being itself—an ever-deepening encounter with the boundless simplicity that rejects inquiry.

Works Cited

Atkinson, James. The Mystical in Wittgenstein’s Early Writings. Routledge, 2009.

Dionysius, Areopagite. Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works. 2nd ed., Paulist Press, 1987.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. 1st ed., Routledge, 1922.