David W. Livingstone, Ph.D.

The following remarks were presented at Vancouver Island University during the “Teaching in the Post-Truth Era” panel on April 12, 2017. I would like to thank the organizers, Dr. Melissa Stephens and Dr. Sonnet L’Abbé, for inviting me to join this interesting and timely panel. These thoughts about liberal education are my own and are not intended to represent the views of VIU or the Liberal Studies Department. Some parts of this essay were presented at the BCPSA annual meeting in 2010, and a longer version of this paper is scheduled to be published on VoegelinView.com in fall 2017.

When one looks at the history of higher education in Canada and the United States it is striking to note that at one time just about every university regarded liberal education as central to its purpose. Moreover, that purpose was connected to, though not entirely limited to, citizenship broadly conceived. At the time of Canada’s founding in 1866, one of the architects of our Constitution, Thomas D’Arcy McGee, argued before a Montreal audience that education is “an essential condition of our political independence.” His understanding of education, the kind of education required for Canadian national identity, came from the “classical sources.”

With some notable exceptions, most of our contemporary publicly-funded universities have drifted from these original goals which have been eclipsed by either vocational training or narrow specialization and research. And in some departments, the notion that a university education ought to be guided by the pursuit of truth is even put into question. I would argue that unless this original purpose is recovered by our institutions of higher education, our society and the individuals who make it up will be culturally, politically, and spiritually malnourished, citizenship will be compromised, and debate about difficult issues will continue to become intellectually thinner and simultaneously shriller.

Liberal education traces its roots back to the ancient Greeks, and to Plato in particular. In the Middle Ages it came to mean an education in the trivium and the quadrivium, together comprising the seven liberal arts: grammar, rhetoric, logic; geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, and music.[1] Liberal education includes aspects of subjects now found separated into the arts and humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. It is an education that methodically and systematically addresses the question of the meaning of life and does so through critical reflection on great works from a variety of “disciplines”: philosophy, politics, science, art, religion. While interdisciplinary, it is an education that nonetheless has a specific, identifiable content. At the “core of liberal education was the duty of the teacher to impart and cultivate those talents and excellences which would prepare a student to bear the obligations of citizenship and to begin the exploration of the intellectual and spiritual life.”[2] While it is possible to obtain a decent liberal education in Canada apart from so-called, “great-books” programs, nevertheless the “multiversity” and its cafeteria-style programming is now the norm, and this represents a shift from higher education a century ago. Liberal education is now but one option available to students. In most Canadian universities the student is left to decide the content of their education, choosing from a bewildering array of courses, some serious and some less so. They must gravely and prudently choose their courses in the absence of the very education intended to cultivate their prudence and gravitas. It’s as if we expect them to know the purpose of higher education before they have any experience of it. It’s no wonder they default to courses that at least (so they think) promise them a path to employment. And so across North America we have seen a decline in enrollments in the humanities and the liberal arts. But what do our students miss by making this choice? And how might our society and our political culture be affected over time by the absence of liberally educated citizenry?

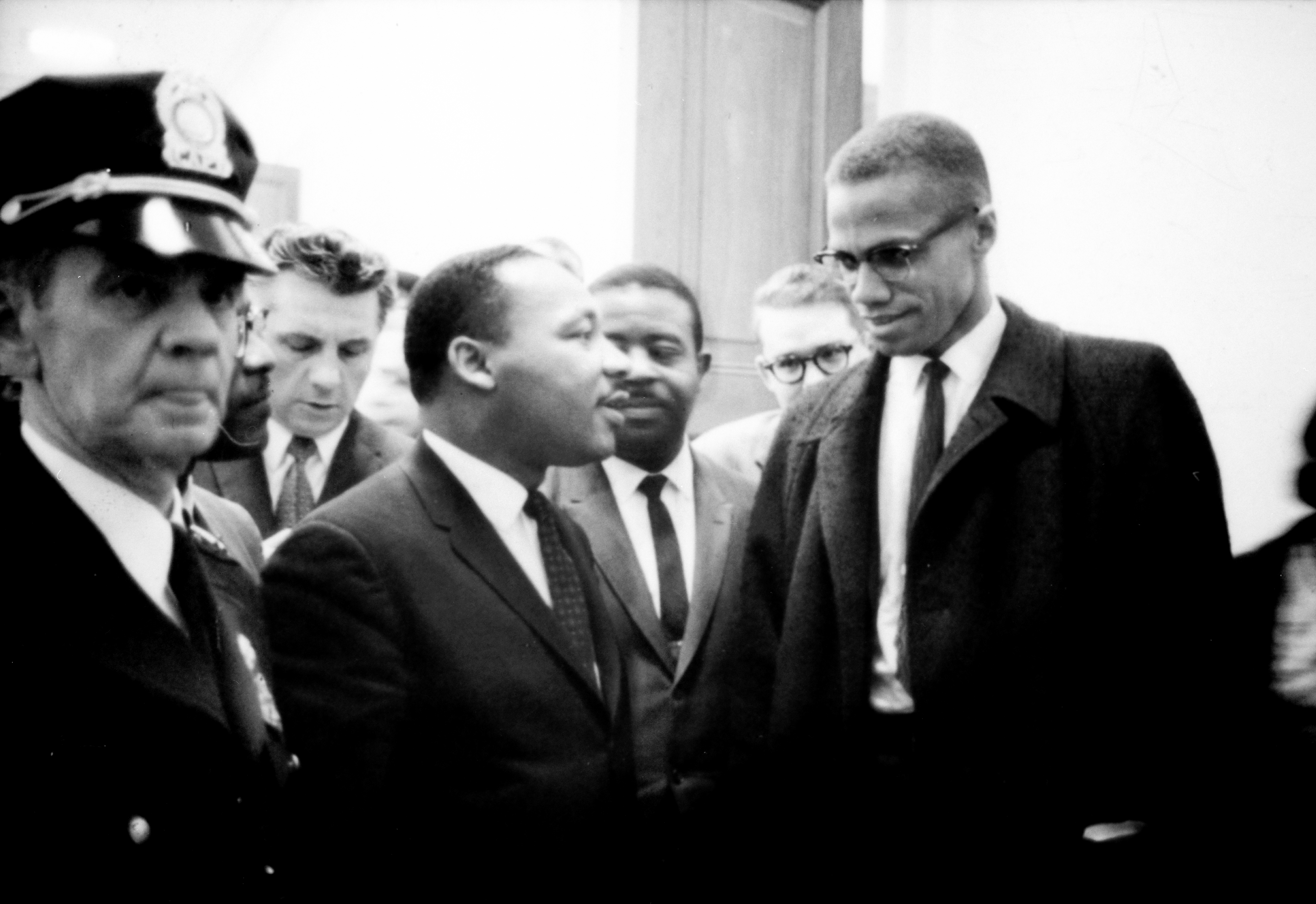

In the early twentieth century, the American civil rights pioneer, W.E. B. Du Bois, was thinking about the purpose of higher education, and particularly what emancipated American slaves would need in terms of education if they were to take their place as free citizens of a democratic republic. He declared that they needed a college that could give them the best that liberal education had to offer. Now that their body was emancipated they would need to free their mind, and they could best do this through the study of the great authors of the past, including, he thought, Aurelius, Aristotle, and Shakespeare. Du Bois opposed Booker T. Washington’s idea that freed blacks needed vocational training first and foremost if they were to become independent. Surely in the final analysis some combination of these two perspectives is required, We shouldn’t downplay our students’ desire to find meaningful work when they graduate, yet university has always been about more than training for work, and it hasn’t always been about preparing activists to change society before they have even considered carefully the principles upon which that society that affords them the freedom to study is built. What Du Bois insists on is that true freedom requires a freedom of the mind from prevailing currents of thought and habits. In particular, Du Bois was concerned that the emancipated blacks in his day would be subsumed into a political economy that would give shape to their minds below the standard of what they should strive for.

“What if the Negro people be wooed from a strife for righteousness, from a love of knowing, to regard dollars as the be-all and end-all of life? What if to the Mammonism of America be added the rising Mammonism of the re-born South, and the Mammonism of this South be reinforced by the budding Mammonism of its half- wakened black millions?”[3]

The ubiquitous concern for money and for utility in America—in any democratic society, really—may crowd out the higher, human concerns. Du Bois shares Aristotle’s view that citizens “must be able to do necessary and useful things, but still more they must be able to do the noble things. Accordingly, it is with these aims in view that they should be educated.”[4] Vocational training and liberal education are both needed, but of these two, liberal education is higher because it aims to illuminate the comprehensive goals and purposes of life to which the vocational tasks serve as means.

Remarkably, Du Bois does not regard the tradition of great texts as one of the causes of black oppression. Rather he regards these books as potential sources of human liberation. In fact, he argued that blacks in the United States would be denied genuine freedom—freedom of the mind—if they were denied access to these avenues of human liberation. For Du Bois, these texts do not enforce distinctions of race or color; there greatness lies in the fact that they transcend these contingent aspects of the human person.

“I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not. Across the color line I move arm in arm with Balzac and Dumas, where smiling men and welcoming women glide in gilded halls. From out the caves of evening that swing between the strong-limbed earth and the tracery of the stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension. So, wed with Truth, I dwell above the Veil. Is this the life you grudge us, O knightly America? Is this the life you long to change into the dull red hideousness of Georgia? Are you so afraid lest peering from this high Pisgah, between Philistine and Amalekite, we sight the Promised Land?”[5]

Du Bois concludes that “the true college will ever have one goal,—not to earn meat, but to know the end and aim of that life which meat nourishes.”[6] Du Bois’ “true college” is jeopardized when it directs itself primarily by standards of utility and so-called relevance. His view of the capacity of liberal education to emancipate the individual is based on the unspoken premise that the truth is what unites us across color lines, and across other features of human personality that make each of us unique. It is not for the purpose of erasing those interesting differences that we ought to pursue this common goal, but simply to set what makes us different within a larger frame of shared, human aspiration and higher fulfillment.

Reflecting on the place of wisdom-seeking in contemporary education Sean Steel, writes that “education, contrary to what is most often said today among reformers, cannot properly by ‘student-,’ ‘child-,’ or ‘learner-centered”; it must be truth-centered. Consequently, its center must lie somewhere between the teacher and the learner….There can be no genuine dialogue between teacher and student where the center is not somewhere between the discussants—if truth rather than either of the participants is not the central concern of both parties.”[7]  Yet this notion, that the truth sits between teacher and learner and unites them in a shared activity benefiting both, has been under attack within the academy for a long time. We certainly have to wonder if this attack on the truth in our institutions of higher learning is at least partly responsible for generating the post-truth era we find ourselves in today.

Yet this notion, that the truth sits between teacher and learner and unites them in a shared activity benefiting both, has been under attack within the academy for a long time. We certainly have to wonder if this attack on the truth in our institutions of higher learning is at least partly responsible for generating the post-truth era we find ourselves in today.

One might say the attack on truth began with the 19th century philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche, who writes: “It is nothing more than a moral prejudice that truth is worth more than appearance. That claim is even the most poorly demonstrated assumption there is in the world. People should at least concede this much: there would be no life at all if not on the basis of appearances and assessments from perspectives.”[8] This Nietzschean perspective is adopted and developed by the influential 20th and 21st Century pragmatist, Richard Rorty. There is nothing that we can know that exists by nature, and indeed nothing has an independent “essence.” Where the classical thinkers may have looked to nature, especially human nature, to learn about our ends and purposes, contemporary “philosophers” teach us instead that this was a fool’s errand based on dogmatic metaphysical assumptions, metaphysics being the search for those unchanging principles of the universe that undergird and hence explain changing realm we inhabit. So Rorty concludes that we should stop being metaphysicians and become “ironists.” The ironist, he explains, “is a nominalist and a historicist. She thinks nothing has an intrinsic nature, a real essence. So she thinks that the occurrence of a term like ‘just’ or ‘scientific’ or ‘rational’ in the final vocabulary of the day is no reason to think that Socratic inquiry into the essence of justice or science or rationality will take one much beyond the language games of one’s own time.”[9] But if there are no natures, then human beings do not have a nature either. This “insight” leads to the conclusion that we must construct meaning in our lives rather than discover it.

According to Rorty, “slogans” like “natural human rights,” concepts that the Canadian founders thought existed and ought to be secured through Constitutional structures, turn out to be nothing more than “handy bits of rhetoric.” They refer to nothing real, nothing in nature. The risk of adopting Rorty’s viewpoint is that it removes the shared goal of pursuing the truth that Du Bois and others believed was the path to true liberation for all human beings. Instead, if we go down the path offered by Rorty and others, we close ourselves off to one another. Our young people, educated to believe that behind so-called truth there lies only masked power can too easily conclude that amassing and wielding power to advance their interests is what matters most. Justice then appears to them to be nothing more than “the advantage of the stronger.” And ultimately we are more apt to become impressed by our differences rather than by what unite us.

So let me conclude by referring to the person I started with, D’Arcy McGee. For though he suffered various forms of bigotry and experienced violent faction, and, sadly, though he was killed by an assassin’s bullet, he expressed high hopes for Canada and its political institutions, provided we citizens focus on what matters. “The object of all intellectual pursuits, worthy of the name,” he said to his Montréal audience, “is the attainment of Truth.” It is the “sacred Temple to be built, or re-built,” and “the Ithaca of every Ulysses really wise.” McGee intended to give future generations of Canadians who were fortunate enough to live under the Constitution he helped craft some sage advice, if only we will recall it and try to live by it:

“Regarding the New Dominion as an incipient new nation, it seems to me that our mental self-reliance is an essential condition of our political independence; I do not mean a state of mind puffed up on small things; an exaggerated opinion of ourselves and a barbarian depreciation of foreigners; a controversial state of mind; or a merely imitative apish civilization. I mean a mental condition, thoughtful and true; national in its preferences, but catholic in its sympathies; gravitating inward, not outward; ready to learn from every other people on one sole condition, that the lesson when learned has been worth acquiring. In short, I would desire to see, Gentlemen, our new national character distinguished by a manly modesty as much as by mental independence; by the conscientious exercise of the critical faculties, as well as by the zeal of the inquirer.”[10]

____

[1] For similar definitions see Anthony Kronman, Education’s End: Why Our Colleges and Universities Have Given Up on the Meaning of Life (Yale: Tale University Press, 2009); Peter Emberley, Waller Newell, Bankrupt Education: The Decline of Liberal Education in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994); Richard Myers, Colin O’Connell, Patrick Malcolmson, Value Relativism and Liberal Education: A Guide to Today’s B.A. (University Press of America, 1996). For a brief look at liberal arts curricula in early Canada, see See R.A. Falconer, “The Tradition of Liberal Education in Canada,” Canadian Historical Review 8, 2, 1927; In the U.S. context, consider Anthony T. Kronman, Educations’ End: Why Our Colleges and Universities Have Given Up on the Meaning of Life (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), chp 2-3.

[2] Peter Emberley and Waller Newell, Bankrupt Education: The Decline of Liberal Education in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994), 3

[3] W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (1908; New York: Bantam Classic text reprinted from the 1953 Blue Heron edition), 57. Prepared for the University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center, http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/DubSoul.html,%20, accessed April, 2017.

[4] Aristotle, Politics, VII, 1333a3l-b4 (emphasis added).

[5] Du Bois, 76.

[6] Du Bois, 58

[7] Sean Steel, The Pursuit of Wisdom and Happiness in Education: Historical Sources and Contemplative Practices (New York: SUNY Press, 2014), 136

[8] Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil , Aphorism 34

[9] Rorty, Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 74-75

[10] McGee, “Mental Outfit of the New Dominion” The Journal for Education of Upper Canada, Vol XX, no.11, 1866, 177.