By Amy Swanson

This artwork, based on The Epic of Gilgamesh, relates to the text’s multiple uses of bathing and dressing as a metaphor for a character’s state of mind or stage of development. There are several such moments in the text. For instance, Gilgamesh’s mother, Ninsun, takes a bath of tamarisk and soapwort before praying to Shamash (III 37-38, 23), and Enkidu’s grooming scene signals his integration into human society (P 107-111, 14). Additionally, when Gilgamesh meets the two main voices of wisdom in the tale, Uta-Napishti and Shiduri, he is in a state of physical dirtiness and dishevelment, and both tell him to bathe. When Gilgamesh finally bathes at Uta-Napishti’s home (XI 255-258, 94), he does it as an act of self-care coinciding with the end of his journey. The cleansing Gilgamesh undergoes signifies his return to mental homeostasis. This metaphor for bathing is apt to describe the human experience, given that creatures who bathe will eventually become dirty again. Dirt can be seen as a metaphor for the “cognitive dirt” that encrusts Gilgamesh after the loss of Enkidu. The accumulation of dirt is a literary device that signifies the fear of death that comes inextricably with mortal life: Gilgamesh will always return to his fear of death, like how he will forever become dirty again. Hence, we know that Gilgamesh does not make a 180-degree turn when he returns home to Uruk (XI 323-XI 329, 96-97).

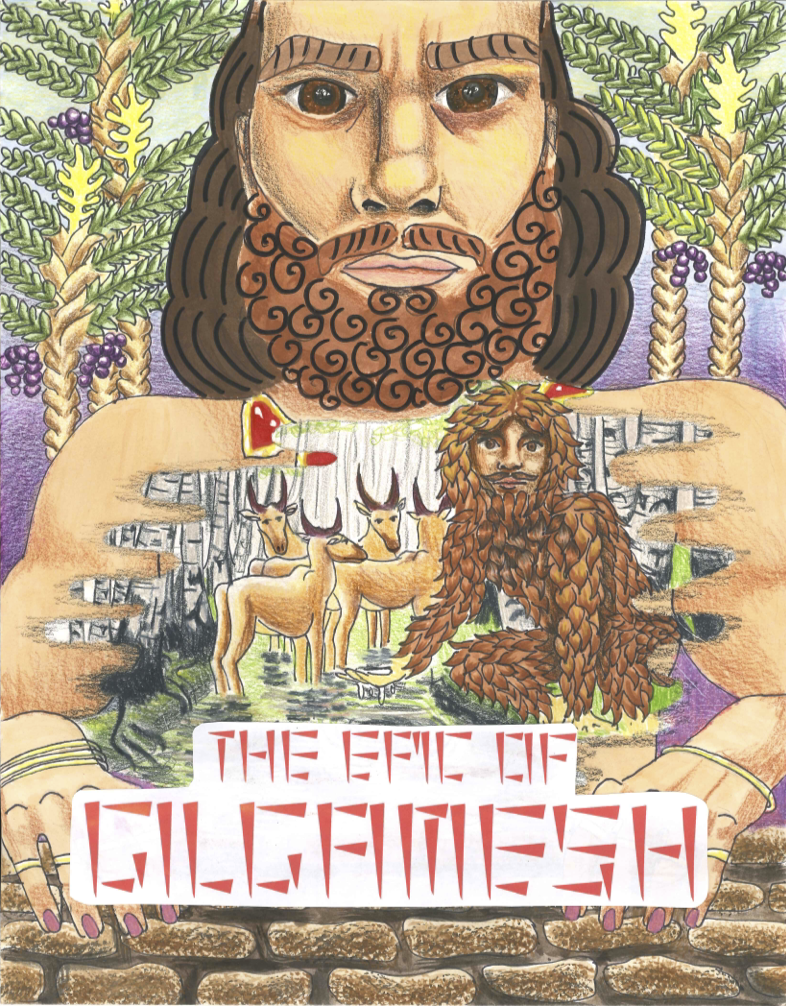

The artwork depicts Gilgamesh upon his homecoming, stationed atop the ramparts he built with the magnificent date palms looming behind him. Inside the opening of Gilgamesh’s chest is a dreamlike image of Enkidu accompanied by a pack of antelopes to indicate the lasting impact that the loss of his friend had on Gilgamesh. This opening depicts the human condition as bearing an always-open wound of loss and fear of death. A core takeaway from the text is the way it invites the reader to judge for themselves the brutish and stubborn Gilgamesh, who, arguably, did not undergo any meaningful character shifts. Some, however, interpret that he undergoes as much of a shift as his feeble, death-fearing mortal soul is capable of—just enough to carry on with his life and return home to Uruk. Depicting Enkidu’s symbolic impression on Gilgamesh’s heart represents this subtle but crucial shift in Gilgamesh. He will never be invulnerable to the psychic dirtying that comes with mortal life, just as he will never forget the loss of Enkidu. However, Gilgamesh’s ability to continue ruling with pride in his accomplishments as the king of Uruk is a testament to the strengthening his character attained as the Epic progresses.

Work Cited

The Epic of Gilgamesh. Translated by Andrew George. Penguin Classics, 2003.