Redeemed Through Disobedience

By Brandon Kornelson

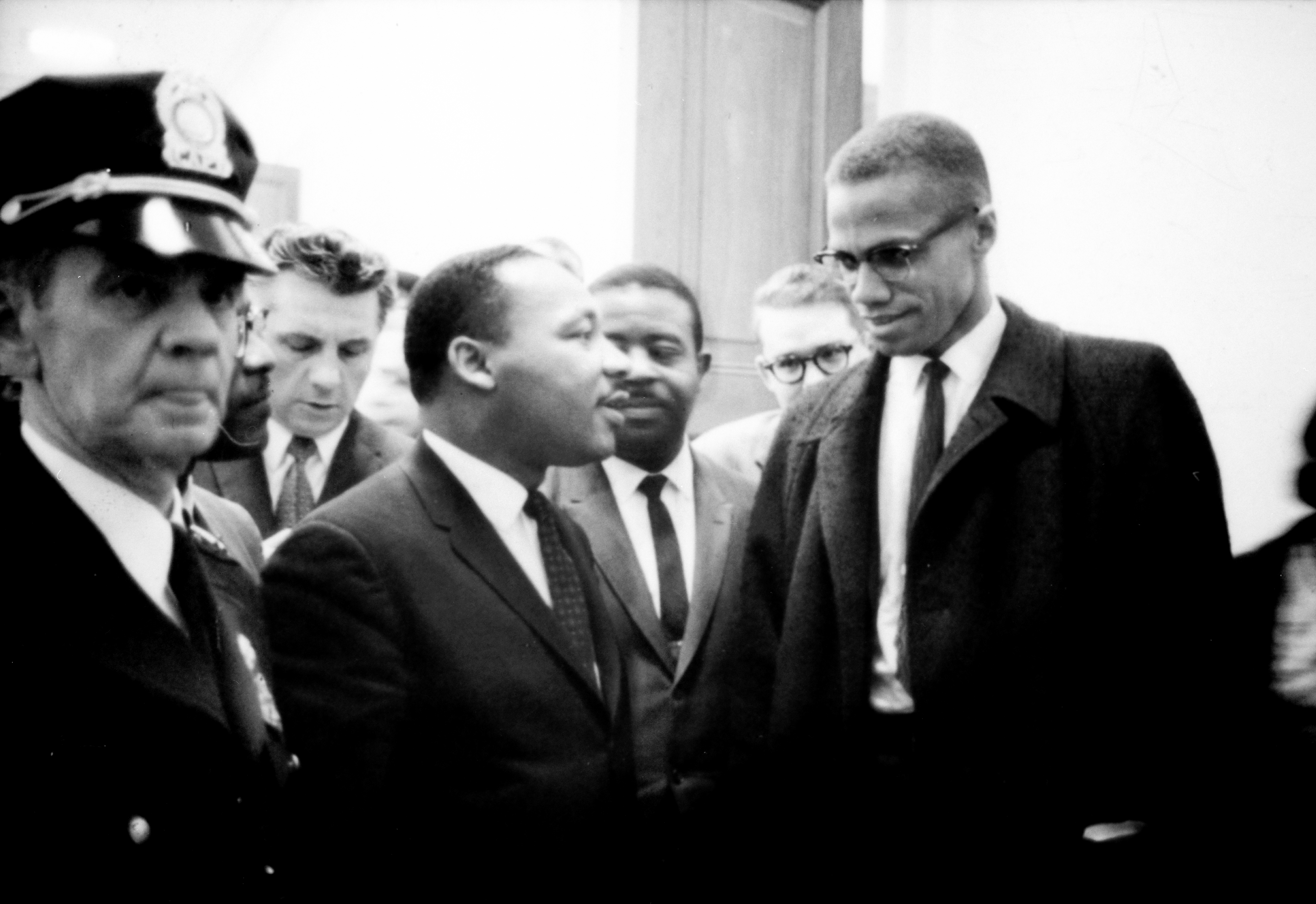

Mugshot of Martin Luther King Jr following his 1963 arrest in Birmingham

While in Birmingham Jail, Martin Luther King Jr. wrote Letter from Birmingham Jail (1963), a powerful letter that responded to some harsh criticism from the local white community who were upset with the “problems” that King seemed to be stirring up. King emphasizes that the “problems” he was stirring up were direct results of the injustice that was being perpetrated against the black community, thus leaving the community no choice but to take action in order to achieve redemption. King’s tactic of nonviolent resistance, which stemmed in part from his roots in his Christian faith,1 played an important role in achieving social justice during the Civil Rights Movement. King understood that the possibility of redemption after years of social injustice was only possible through direct nonviolent action.

◊ Read the rest in .pdf, or below ◊

In Christian belief, redemption is most often understood as the process of an individual or a group who receives compensation for, or achieves salvation from, “evil” or “sin.” For example, Christ sacrificed himself to redeem humanity from their sinful nature. In this metaphoric example, the only thing that could provide legitimate redemption for humanity’s condition was suffering and sacrifice. King’s ideas of redemption for the black community represent some striking similarities to the story of Christ. King understood redemption as something that could be achieved through sacrificial nonviolent resistance and the suffering that came with it. In King’s eyes, nonviolent resistance is a tactic designed to seek friendship from his enemies, rather than to defeat or humiliate them (Hunt 245). In King’s words, “[i]t is evil that the nonviolent resister seeks to defeat, not the persons who are the perpetrators of evil” (qtd. in Hunt 245). Further, “[t]he nonviolent resister… realizes that [his/her nonviolent protests] are not ends themselves; they are merely means to awaken a sense of moral shame in the opponent. The end is redemption and reconciliation” (245). However, King also understood that in the struggle against evil, suffering accompanies the process of redemption. King understood that to achieve redemption he had to accept violence from his enemies without retaliating. “‘Rivers of blood may have to flow before we gain freedom, but it must be our blood,’” King claims, quoting Mohandas Gandhi (246). In addition, King also understood the absolute necessity of both nonviolence and suffering to achieve redemption: “My personal trials have also taught me the value of unmerited suffering. … Recognizing the necessity of suffering, I have tried to make of it a virtue. … I have lived these last few years with the conviction that unearned suffering is redemptive” (247). Therefore, King’s ideas of redemption required the black community to carry a heavy burden of suffering and sacrifice, much like the story of Christ.

King had a deep conviction in the inherent equality of all of humanity, a conviction that was influenced by his Christian faith (Hunt 242). His philosophy of nonviolence has its deep roots in the triad of theology, fellowship, and faith (227). Through these conceptions, King developed a “‘serious intellectual quest for a method to eliminate evil’” (qtd in Hunt 227) which led him to his aspiration of the ultimate form of redemption, which was to be achieved by establishing what he calls the “Beloved Community” (227). King’s vision of the Beloved Community has its roots in his deep faith and theological convictions of Jesus’ idea of the Kingdom of God. When the US Supreme Court outlawed racial segregation on the transportation systems after the successful Montgomery Bus Boycott, King stated that a main end goal of the Civil Rights Movement was “the creation of the Beloved Community” (Inwood 493). For King, the Beloved Community was something that could only be achieved through nonviolence; he did not see nonviolence as an end, but rather as a means to appropriate the Beloved Community (Hunt 243). In addition, King was influenced by philosopher Friedrich Hegel who suggested that conflict is necessary for social change to occur; and “that conflict, [if] properly managed, can ground faith and hope for the future” (244). However, it is clear that King emphasized the necessity of nonviolence as being the only means to grasp the end goal of redemption and the Beloved Community.

At the beginning of King’s Letter From Birmingham Jail (1963), King sheds light onto an alternative perspective for his criticizers to see. He agrees with his criticizers that it is unfortunate that nonviolent demonstrations are occurring and disrupting the peace in Birmingham; however, he then continues to outline the sociological realities of the white supremacist power structures that gave birth to the demonstrations in the first place. King claims that these racist structures of power gave the black community no choice but to take action. King states: “Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue… [which can] no longer be ignored” (para. 9). That the white community had been frustrated with King demonstrates that King’s tactic was successful. However, legalized racial segregation in America had created a tense social and political atmosphere; the experiences of injustice within this tense context fostered bitterness and hatred amongst members of the black community. King understood that when minority groups are ostracized, marginalized, and oppressed, social environments are created that become ripe for the harvest of radical violent ideological movements. Although King acknowledges that “violence has a certain cleansing effect” (qtd. in Inwood 504), he believed that violence perpetuates fear and vengeful punishment, which is counterproductive and creates the same conditions that the black community has endured, only for others (Inwood 504). “The aftermath of nonviolence is the creation of the Beloved Community, while the aftermath of violence is tragic bitterness,” King claims (qtd. in Hunt 245). In other words, King knew that violence would destroy exactly what it was meant to achieve. However, with the oppressed black community, King also fully understands that “[if their] repressed emotions are not released in nonviolent ways, they will seek expression through violence” (para. 24). Thus, while understanding that violence was inevitable if oppression was not challenged, King sought to “transform the suffering [of the black community] into a creative force” of nonviolence (qtd. in Hunt 247).

King claims in his letter that “freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed” (para. 11). In other words, power does not dismantle itself; on the contrary, it does everything it can to preserve itself. Therefore, it was up to the black community (the oppressed) to demand equality and liberation from their oppressors. Redemption from structures of power that are responsible for injustice is not possible unless the structures of power are directly confronted, challenged, and either dismantled or reformed from exterior forces. In addition, King explains that it is our “responsibility to disobey unjust laws,” as he reminds the reader that laws are not inherently based on justice, giving the example of the horrific legalized policies of Nazi Germany (para. 18). In explaining this, King contrasts the view that laws are always based on justice, and he demonstrates that it is morally justified to challenge and break unjust laws; if these unjust laws are not broken, injustice and oppression will continue, inevitably manifesting into more tension and conflict.

King’s letter addresses his profound disappointment with what he calls the “white moderate,” a term he uses to refer to the person who does – and prefers to do – nothing, and who is committed to “order” rather than justice, because, in King’s mind, redemption is only possible through direct action. “We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people, but for the appalling silence of the good people,” King claims (para. 21). Towards the end of his letter, King outlines this point further in a core statement that illustrates the message that redemption must be achieved through action: “I have tried to make clear that it is wrong to use immoral means to attain moral ends. But now I must affirm that it is just as wrong, or perhaps even more so, to use moral means to preserve immoral ends” (para. 35). What King is describing in this quote is that failure to take action against injustice is itself injustice; neutrality is an illusion during times of injustice, and remaining silent in the face of “evil” makes you complicit with acts of injustice. Indeed, for King, the oppressed can only be redeemed when the oppression is directly confronted.

Contrary to common belief, it is worth noting that what ought to be emphasized when we discuss, write about, and remember the Civil Rights Movement, is that King’s nonviolent strategy was mainly a tactic. King and many other nonviolent activists did not embrace a 100% nonviolent lifestyle. On the contrary, they owned weapons, and they guarded their communities as preparation for violent resistance if they were attacked. For example, when journalist William Worthy had visited King’s home, he went to sit down on an armchair, and almost sat on two pistols. “Bill, wait, wait! Couple of guns on that chair!” yelled Bayard Rustin, a nonviolent activist (Cobb 7). Rustin questioned King about the guns, and King responded that they were “[j]ust for self-defense” (7). Indeed, it was no secret that many civil rights activists, such as King, were well armed in order to protect themselves and their families: local law enforcement and the federal government refused to provide adequate protection for them (Cobb 7-8). Glenn Smiley, a man who gave advice to King during the Montgomery Bus Boycott, had claimed that King’s home was “an arsenal” (Cobb 7-8). These anecdotes outline one aspect of the Civil Rights Movement that is often overlooked: the campaign of nonviolence was integrated and supported by a campaign of armed defense. Indeed, as civil rights scholar and author Charles Cobb demonstrates in his book This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed, violence played an essential role in the Civil Rights Movement and the redemption of the black community (187). For example, Cobb writes of a heavily armed resistance group called “Deacons for Defense and Justice” who were committed to protecting the nonviolent movement (192-193). Further, another example that demonstrates this collaboration of the nonviolence movement with armed resistance is that although black activists from the group CORE – Congress of Racial Equality – were committed to nonviolent principles, they also received protection from armed defenders (196-197). In other words, violent and nonviolent groups, who were dedicated to the same goals of redemption, corresponded with one another to create a successful alliance and strategy for social change. The nonviolent campaigners needed the armed defenders to protect their movements, and the violent campaigners needed the nonviolent resisters to lead the path to redemption, as true redemption could only be achieved through nonviolence. Nonviolent activist Fred Brooks highlights this alliance by stating that “[a]ny time we were having a demonstration [armed defenders] would be standing there on both sides of the street. Wherever we went it was like a caravan; these guys in their pickup trucks with… rifles up in the back” (196-197). Charlie Fenton, a dedicated nonviolent white activist with CORE, was confronted with this merge of armed and nonviolent resisters when he arrived at the Jonesboro Freedom House. The house had become an armed camp. Although this disappointed Fenton greatly, he quickly realized the necessity of the arms; without the armed men in Jonesboro the nonviolent movement would have been violently destroyed by white supremacists (200-201). Some nonviolent activists questioned the compatibility of having armed defenders involved in the nonviolent movement; however, as racist violence began to surge, so did the agreement on the necessity of armed defense as being crucial to the movement (Cobb 197-198). In Cobb’s words, “nonviolence and armed resistance are part of the same cloth; both are thoroughly woven into the fabric of black life and struggle” (240). The armed defense component of the movement managed to create spaces of relative sovereignty, which ultimately allowed the nonviolent component to succeed in its mission of redemption.

Martin Luther King’s method of nonviolent resistance was a thoughtfully constructed strategy to achieve redemption. The objective for King was never to harm, destroy, defeat, or humiliate his enemies; rather, his objective was to embrace his enemies with love in an attempt to persuade them to change their position on the unjust status quo that was represented within the socio-political system (Hunt 245). For King, the achievement of redemption was only possible through direct nonviolent confrontation with legalized injustice through a process of consciously disobeying, undermining, and rebelling against unjust laws. As history has shown, King’s strategy was successful in changing the legalized racism in the US. However, the legacy of racism continues to systemically haunt US political structures.

Notes

- While King’s tactic of nonviolent resistance draws in part from his roots in the Christian faith, he was also heavily influenced by the philosophies of Thoreau, Hegel, Rauschenbusch, Gandhi, and his family (Hunt 243-244).

Works Cited

Cobb Jr., Charles E. This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible. Basic Books. 2014. EPUB file. 11 April 2016.

Hunt, C. Anthony. “Martin Luther King: Resistance, Nonviolence and Community.” Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 7.4 (2004): 227-251. Web. 25 Apr. 2016.

Inwood, Joshua F. “Searching for the Promised Land: Examining Dr Martin Luther King’s Concept of the Beloved Community.” Antipode 41.3 (2009): 487-508. Web. 25 Apr. 2016.

King, Martin L. “Letter from a Birmingham Jail [King, Jr.].” African Studies Center. 16 Apr. 1963. Web. 25 Apr. 2016. <http://www.africa.upenn.edu/Articles_Gen/Letter_Birmingham.html>.