By Vania Zanetti

In the book Alternative Narratives in Early Childhood: An introduction for Students and Practitioners, Moss (2019) speaks to the idea that the vocabulary we use in early childhood spaces shapes early years practices and experiences. Moss suggests that the dominant language of the early years narrative is “instrumental, calculative and economistic, technical and managerial, dull and lifeless” (p. 81). This makes me thoughtful about theoretical influences that inform the choices that educators make and ultimately shape what is imagined for early childhood spaces.

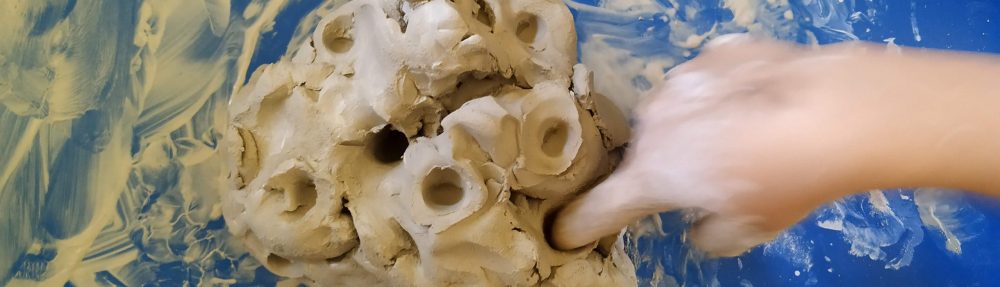

With the image above I am intrigued to think about the language used to create environments for children. I imagine conversations about safety and regulations that stripped aged trees of lower branches to keep children from scaling higher than they “should”. I wonder, ‘How often, and why, are toys and equipment chosen in early childhood settings because they include words such as safety, quality, durability, and development?

As an alternative to the dominant narrative Moss offers the language used in Reggio Emilia. The language is almost dream-like with a narrative that uses words like exploration, possibility, imagination, and becoming. It makes me wonder about the multiple ways spaces can provoke exploration, project making, and pathways for growth and development. I’m curious about connections to the Early Learning Framework (Government of BC, 2019, p. 77) and welcome the invitation to engage with the critically reflective question, “What opportunities do children have to access materials that can be transformed or investigated?”

I wonder how we can nurture alternative dialogues about children’s spaces. How might these dialogues be informed by the first principle listed in the Early Learning Framework (Government of BC, 2019), “Children are strong, capable in their uniqueness, and full of potential” (p. 15)? What kinds of worlds might become possible?

References:

Government of British Columbia. (2019). British Columbia early learning framework (2nd ed.). Victoria: Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Children and Family Development, & British Columbia Early Learning Advisory Group. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/early-learning/teach/early-learning-framework

Moss, P. (2019). Reggio Emilia: A story of democracy, experimentation, and potentiality. In Alternative narratives in early childhood: An introduction for students and practitioners (pp. 81). New York, NY: Routledge.