By Sabrina B. E. Limas Camacho and Julie Kliauga

By Sabrina B. E. Limas Camacho and Julie Kliauga

By Vania Zanetti

In the book Alternative Narratives in Early Childhood: An introduction for Students and Practitioners, Moss (2019) speaks to the idea that the vocabulary we use in early childhood spaces shapes early years practices and experiences. Moss suggests that the dominant language of the early years narrative is “instrumental, calculative and economistic, technical and managerial, dull and lifeless” (p. 81). This makes me thoughtful about theoretical influences that inform the choices that educators make and ultimately shape what is imagined for early childhood spaces.

With the image above I am intrigued to think about the language used to create environments for children. I imagine conversations about safety and regulations that stripped aged trees of lower branches to keep children from scaling higher than they “should”. I wonder, ‘How often, and why, are toys and equipment chosen in early childhood settings because they include words such as safety, quality, durability, and development?

As an alternative to the dominant narrative Moss offers the language used in Reggio Emilia. The language is almost dream-like with a narrative that uses words like exploration, possibility, imagination, and becoming. It makes me wonder about the multiple ways spaces can provoke exploration, project making, and pathways for growth and development. I’m curious about connections to the Early Learning Framework (Government of BC, 2019, p. 77) and welcome the invitation to engage with the critically reflective question, “What opportunities do children have to access materials that can be transformed or investigated?”

I wonder how we can nurture alternative dialogues about children’s spaces. How might these dialogues be informed by the first principle listed in the Early Learning Framework (Government of BC, 2019), “Children are strong, capable in their uniqueness, and full of potential” (p. 15)? What kinds of worlds might become possible?

References:

Government of British Columbia. (2019). British Columbia early learning framework (2nd ed.). Victoria: Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Children and Family Development, & British Columbia Early Learning Advisory Group. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/early-learning/teach/early-learning-framework

Moss, P. (2019). Reggio Emilia: A story of democracy, experimentation, and potentiality. In Alternative narratives in early childhood: An introduction for students and practitioners (pp. 81). New York, NY: Routledge.

By Students in Practicum II, Ocean Kneeland, and Antje Bitterberg

Creating the event:

The public event ‘Collaborative Dialogue – Learning together and building relationships: A professional development opportunity for early childhood education students, mentors, and curious educators’ is a series of three events imagined and created in collaboration between the VIU ECEC Program and three regional CCRRs: Cowichan, PacificCARE in Nanaimo, and Powell River. When we began to imagine this event, it was important to us to create a space for ongoing dialogue that could hold all of us – students, educators, instructors, and community members in and across our regions. We decided that a series of online events, rather than one, would allow us to nurture a space for dialogue and connections over time. We will share a definition of collaborative dialogue from the Early Learning Framework (Government of BC, 2019), our process for continuing the conversations after the event, and offer some traces of our conversations.

Collaborative Dialogue:

“Collaborative dialogue means inviting comments, questions, and interpretations from children, families, colleagues, and community members to elicit multiple perspectives. This process opens avenues for discussion not to find answers but to explore the different ways of thinking about pedagogy, and to invite reflection on assumptions, values, and unquestioned understandings. Ongoing collaborative dialogue can enrich and deepen perspectives, and can challenge educators to consider new ways of seeing, thinking, and practising.”

(Government of BC, 2019, p. 50)

Revisiting the event with students:

To invite students to reflect on the ‘Collaborative Dialogue’ event, we (Ocean and Antje) visited the students in their practicum seminar a week after the event. We wanted to express our deep gratitude to the four first-year students who shared their pedagogical narrations at the event. We also wanted to acknowledge the students in the audience and their contribution to creating a lively and welcoming space for their peers. In conversation with all the students and their instructor, we learned that many of us embraced uncertainty and an openness to experiment together. Below are two images we created with students to describe what was most meaningful to them.

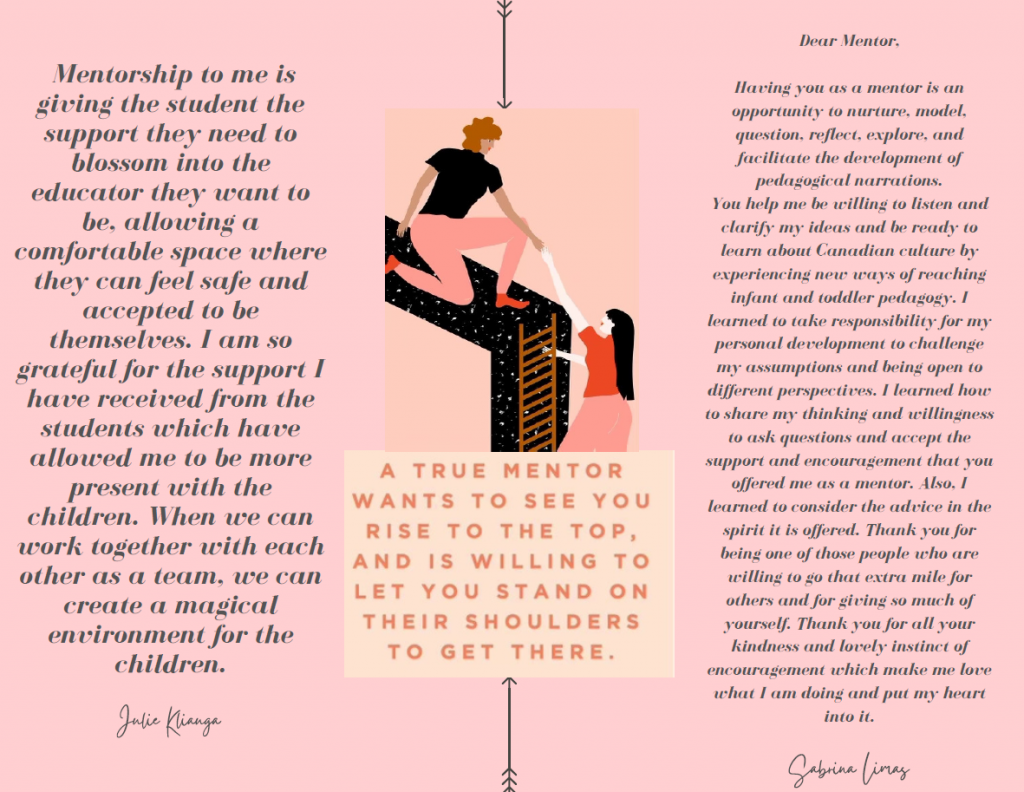

Students who offered their work at the event shared these reflections:

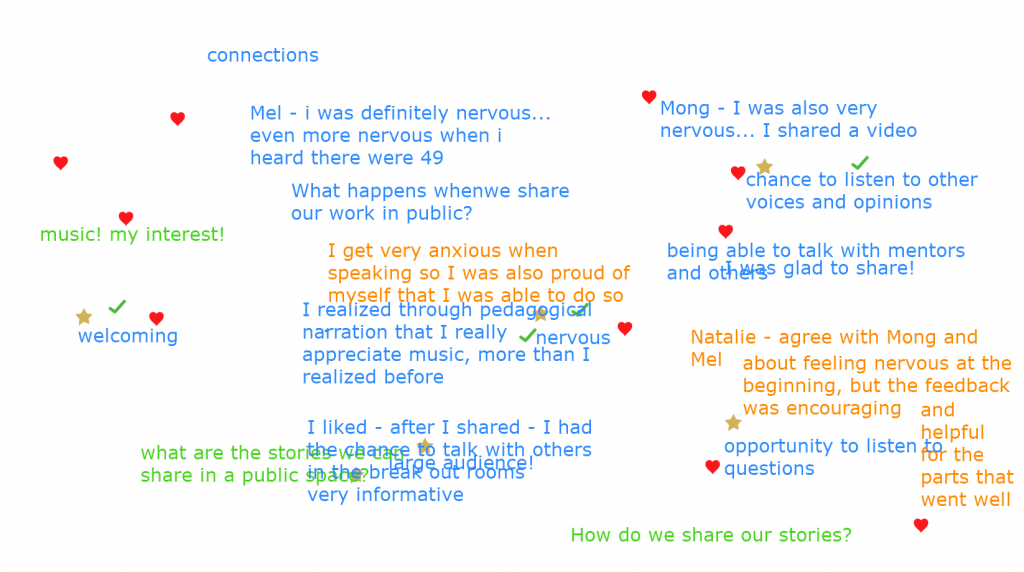

Students who listened and engaged in the event shared these reflections:

Continuing the Dialogue:

We invite you to share your response to our post or the event by submitting a comment! You might also share your ideas and hopes for future events. What are you curious about and what kinds of professional development opportunities are meaningful to you?

Reference:

Government of British Columbia. (2019). British Columbia early learning framework (2nd ed.). Victoria: Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Children and Family Development, & British Columbia Early Learning Advisory Group. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/early-learning/teach/early-learning-framework

By Rachel Phillips

This post was originally published on Rachel’s student blog in February 2020.

From the moment I leave my front door, I can hear the sound of the water rushing down, the sound is encompassing, and immediately connects me to its natural surroundings. I cannot recall the last time I was out for a walk on my own. Carving time out to allow for this escape into the woods, just beyond my yard, required my full intent. It’s myself, my dog Katie, and my thoughts on values I embody as an Early Childhood Educator: respect, relationship, connection, curiosity.

My thoughts are inspired by the pedagogy of listening described by Carlina Rinaldi and foundational to the vision of the Early Learning Framework [ELF] (Government of BC, 2019): “Listening as sensitivity to the patterns that connect, to that which connects us to others; abandoning ourselves to the conviction that our understanding and our own being are but small parts of a broader, integrated knowledge that holds the universe together” (p. 48.). While I’m walking, searching for inspiration, and listening to the many streams, rivers, and sounds of rushing water, I realize that respect, relationship, connection, and curiosity are values that we share as educators that can only be achieved through the act of listening, our abilities to form relationships depend on it.

The curriculum scholar and author Ted Aoki (2011) has influenced many educators in reconceptualizing curriculum. In Curriculum in a New Key he writes about what listening means for a teacher, suggesting her responsibility to the children:

“But she knows deeply from her caring for Tom, Andrew, Margaret, Sara and others that they are counting on her as their teacher, that they trust her to do what she must do as their teacher to lead them out into new possibilities, that is, to educate them. She knows that whenever and wherever she can, between her markings and the lesson plannings, she must listen and be attuned to the care that calls from the very living with her own Grade 5 pupils.” (Aoki, 2004/2011, p. 161.)

Early Childhood must have educators who are listening. Children’s trust in us is cultivated through how well we listen. Listening to the child’s hundred languages forms strong connections, and opens new possibilities for learning. When children feel heard, valued, and supported they can connect to their learning through these relationships and meaningful work. Educators need to notice more about the child than what appears obvious, and what might be shared in verbal language. In a culture of research, educators can listen to the hundred languages of children, and (un)intentionally enact what they value by being compassionate and inviting a sense of wonder.

“Educators are not imposing their ideas on the children, but truly recognizing the children and their efforts. In a way, it is like viewing a child through new eyes. It is challenging to really listen and get to know a child anew and to resist previous ideas of who that child is. Through carefully and intentionally noticing children and what they do, educators have an opportunity to wonder at what they are seeing and hearing.”

(BC Early Learning Framework, 2019, p. 57)

References

Aoki, T. T. (2004, 2011). Curriculum in a new key: The collected works of Ted T. Aoki (W. F. Pinar & R. L. Irwin, Eds.). Lawrence Erlbaum, Routledge.

Government of British Columbia. (2019). British Columbia early learning framework (2nd ed.). Victoria: Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Children and Family Development, & British Columbia Early Learning Advisory Group. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/early-learning/teach/early-learning-framework

By Heather Wilson

After watching the TED talk video, Reclaiming the Honourable Harvest by Robin Kimmerer (2012), I could not stop thinking about a statement she made. She said, ‘… a boy was raised by a river.’ And further questioned if there were two meanings in that statement – was the boy near or reared by a river? Now that I have reflected on that statement, with my own knowledge and experience, I would say that ‘a boy raised by a river’ was just as near it, as he was reared by it. If the boy had the time and freedom to wander and wonder… Where would the boy go to play? Where would he go when he was bored? Where would he want to take his friends? Where would he go to explore? Where would he go for adventure? Where would he go when his soul needed soothing? To the river.

My role as an ECE would be to create time and space for children to become familiar with the land. There is much excitement in the novel experiences, but there is depth, layers and the richness of the child’s own knowledge when they are in a familiar place. Only once this familiarity is there, do children begin to connect with the land, when they are influenced, loved, and raised by that space. In the Early Learning Framework [ELF] (Government of BC, 2019) there is reference to this idea, “Providing time, space, and materials rich with possibilities for experimenting, imagining, and transforming allows children to create and explore…” (p. 75).

There is depth to these questions once you start unpacking them. My role as an ECE seems clear, but what challenges are we facing? Children come from many different families and thus different cultures and perspectives, how do we connect children who would prefer to be connected to a screen or game? When it comes to Infants and Toddlers, how do we explain to families that they are capable of walking a trail, exploring a forest/beach/field/rocks/dirt and connecting with it meaningfully?

Robin Kimmerer spoke and wrote beautifully, and I really appreciate her nine responses to the gifts of the earth:

I am wondering how Kimmerer’s nine responses to the gifts of the earth invite me to think with/about the pathway “Every child is a gift” (Government of BC, 2019, p.66) as offered in the ELF’s Living Inquiry Well-being and Belonging? How might we meet and receive children as gifts? How might we give meaning to the statement, “every child is a gift?” in our daily encounters with children? How might we show our love, appreciation and responsibility to the children in our care?

References

Government of British Columbia. (2019). British Columbia early learning framework (2nd ed.). Victoria: Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Children and Family Development, & British Columbia Early Learning Advisory Group. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/early-learning/teach/early-learning-framework

Tedx. (2012, August 18). Reclaiming the Honorable Harvest: Robin Kimmerer . YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lz1vgfZ3etE&feature=youtu.be

By RoseMary Antony

Growing up in the Middle East I never had many opportunities to explore the outdoors due to harsh desert weather. As I grew up, adapting to indoor life became a part of me and my comfort zone. When I reached B.C, I was blown away by the endless outdoor adventure possibilities. This picture is from my daily walk to Buttertubs Marsh in Nanaimo.

I love listening and using my auditory skills, be it listening to people, music or the sound of crashing waves at the beach, or distant wind chimes on a windy day. One of the first things I did during my early Fall walk at Buttertubs Marsh was to pause, close my eyes and listen. I could hear the frogs croak, ducks splashing and quacking in the water, lizards and small creatures scurrying across tall grass, insects buzzing around my ears, the soft leaves swaying as the gentle breeze blew, all this while feeling the bright sun on my face.

I slowly opened my eyes and looked around to make myself aware of my surroundings again. The Early Learning Framework reminds me that, “Learning is not an individual act but happens in relationship with people, materials, and place” (Government of BC, 2019, p.65). Since spending quality time outside is a relatively new concept for me, I am equally curious and amazed by the novelty of nature and excited to collaborate and engage in reciprocal learning with children.

In A Pedagogy of Ecology, Ann Pelo (n.d.) discusses the significance of developing an ecological identity. She writes, “To foster a love for a place we must engage our bodies and our hearts – as well as our minds – in a specific place” (Pelo, n.d.). As a teacher/researcher, I am inspired by this idea, and wonder what it feels/looks/sounds like to respectfully explore a place with young children. How might children lead us when it comes to exploring the great outdoors? Which paths might become visible? What meaningful experiences could be magnified?

References

Government of British Columbia. (2019). British Columbia early learning framework (2nd ed.). Victoria: Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Children and Family Development, & British Columbia Early Learning Advisory Group. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/early-learning/teach/early-learning-framework

Pelo, A. (n.d.). Rethinking Schools. A pedagogy for ecology. https://rethinkingschools.org/articles/a-pedagogy-for-ecology/

Written by Catherine Chinn

The idea of ‘play’ has such a broad meaning and can involve many different experiences. In this post, I will focus on the following question:

How might broadening the vocabulary around play invite different modes of being in an infant/toddler room?

The BC Early Learning Framework [ELF] (Government of BC, 2019) describes that “play can be individual, collective, spontaneous, planned, experimental, purposeful, unpredictable, or dynamic” (p. 24). Play is vital to children’s well-being, learning, and growing. It is helping children to make sense of their world.

The ELF emphasizes the importance of play and opportunities for children to “experience the world through seeing, feeling, touching, listening, and by engaging with people, materials, places, species and ideas” (p. 24). Educators help create the spaces for play by providing materials and giving opportunities for the children to have meaningful experiences. Something that really resonated with me during the reading was Adrienne Argent’s quote, because it helped me realize that we truly are in an ongoing process of transformation and becoming. Our lived experiences entangle us in this process of becoming.

“To say that we play together is an unjust oversimplification: Rather we are in an ongoing process of becoming… Our curriculum is lived out daily; it exists with[in] all of us. Clay, paper, materials, children, educators, objects, music… are all powerful forces and they bring forth movement, history, and multiple layers of meaning” (Argent, 2014, p. 848, as cited in Early Learning Framework, Government of BC, 2019, p. 25).

As I am broadening the definition of play, I am drawn to the concept of a rhizome introduced in the ELF. A rhizome is a plant that sends underground shoots off in many directions with no predictable pattern. Considering play as rhizomatic, I begin to imagine that play and learning have no predictable pattern and can occur is so many different ways and environments. The ELF discusses that “thinking of learning as rhizomatic leads to understanding that learning cannot be predetermined or have a prescribed outcome but is always producing something new” (p. 25).

References

Government of British Columbia. (2019). British Columbia early learning framework (2nd ed.). Victoria: Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Children and Family Development, & British Columbia Early Learning Advisory Group. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/early-learning/teach/early-learning-framework